David Squires Illustrated History of Football is a laugh-a-minute look back through the game, from its beginnings in the stone age to Leicester City’s victory in the Premier League. The books 184 pages are devoted to covering 92 points in footballing history from stone age man through to Leicester City’s victory in the Premier League in the 2015-16 season. Each point is given two pages, one of written text and one cartoon strip.

I read David Squires Illustrated History of Football for the first time, during lockdown. I remember it well. I was on furlough, the children were at home. It was difficult to maintain my sanity and sense of purpose at times. The incarceration, the sun shining endlessly and the kids playing in the garden. In this context reading Squires comic offering was sweet relief. As I kept my eyes on the kids, sat in the sun on the garden bench, I kept laughing out loud as I made my way through the book. I don’t know if it was just the need to express some kind of emotion, or just the quality of the humour in the book.

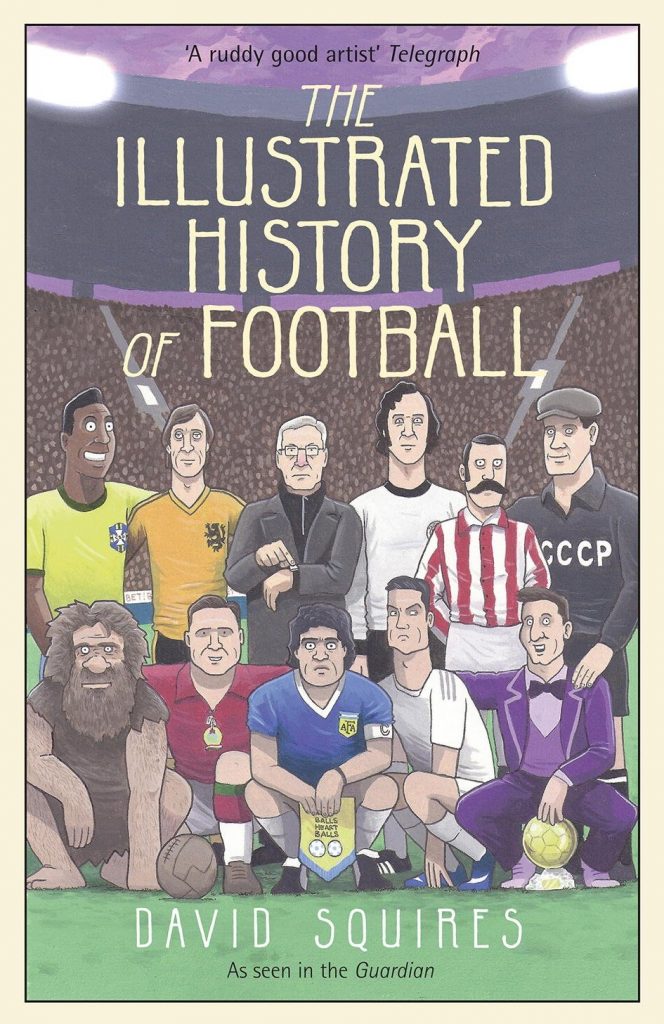

The comedy and jokes are brilliant. My laughing was so loud it could be heard over the fence, but there was so much in it to remind and amuse me of the past, that I felt unashamed and proud in my public display of delight. Subtle humour seeps out of the detail of everything Squires sketches. You only need to scan the front cover: Fergie with drinker’s nose and looking at his watch, Ronaldo turning his back to Messi, Messi posing unashamed in his purple tuxido and Maradona with shot eyes.

The precision, humour and wit that David Squires is able to convey in his comic strips comes across as equally strongly in the prefaces to his comic strips, which are usually a page long. I don’t know if Squires has ever been tempted to just ‘write’ but he’s clearly got the talent to write a book, and you do wonder if he could even attempt some kind of stand-up or take his comic writing abilities to other arenas.

I wonder if the book would be as funny to people who were not of the same generation as Squires. Many, though not all, of the jokes are in-jokes, which you would only get if you were born in the seventies or before. If like me, you were born in the seventies, and were a football nut through most of your childhood, then there’s something spiritual and soulful about perusing the pages of Squires offering. Squires is one of us and he writes for us. In fact his experiences and memories are spookily close to mine. He first became interested in football in the 84/85 season. He quips about having tried cherry coca cola for the first time in 86, and rather spookily, mirroring my own life, trying it again in 2010, and finding it wasn’t quite as good as he remembered.

When I had finished reading the book I had put it down and thought, well that was pretty funny. But as I’ve read through and analysed what it is that I’ve enjoyed about it, I’ve realised that besides being very funny, it has been an incredibly intimate and emotional ride through football history. It was as if it was written for my generation, well it was written for my generation, just because many of the contemporary themes that Squires draws parallels with, when running through the history of football, far from being contemporary span from the 80s to the present day. In other words, this is book is, partly, an in-joke, or it has a lot of in-jokes in it, but you will only get the jokes if your life, like Squires’, started in, at least, the seventies.

He is constantly using any opportunity he can, to draw parallels and make connections, between the past and more recent history or the present, usually in a sarcastic way, which allows him to suddenly switch the frame of the cartoon. In this way, for example in his account of the match between England and Italy in 1934, he uses the fact that the match was played at Highbury to segue way from the match to taking the piss out of the antics of the Arsenal team in the George Graham era.

Squires treatment of history is concise, fascinating and educative. But it also has an angle. Squires luxuriates in bringing to the foreground everything that FIFA, football club communications directors and football’s leading broadcasters would like to forget about. He takes potshots at Newcastle fans, by imagining how things could have gone wrong if they had been in the 1923 FA Cup final rather than Bolton and West Ham, when a white horse called Billy gracefully pushed back the fans to get the game going. Here, he pits our romantic notion of the game, as portrayed by the photos of the horse, his rider and the fans, against the sometimes violent thuggery, suggested by a Newcastle fan, with a scarf over his face to hide his identity, determined to have a fight with said horse. It is this to and fro between the romantic myths and the unpleasant reality, that makes Squires work so appealing and humorous. He is constantly smashing down the purist myths of football by subverting historical accounts or sometimes just enlightening the reader as to what was really going on.

He smashes any notion we might hold that the game was purer and kinder in the olden days. For example, of Preston North End, the inaugural winners of the League in 1888, Squires reveals:

In an act unthinkable from a football chairman, their owner, Billy Sudell, was imprisoned for embezzling funds from the cotton mills he managed to pay his players.

It is both a love of football that shines through, but also a devastating non-stop critique of all aspects of the game. Football both disgusts and delights.

Squires treatment of the absurdities, terminology and idiosyncrasies of the modern game is sophisticated. He creates fictional historical metaphors, which he inserts playfully into his histories:

From the dawn of human existence, across every continent, human beings have been playing some form of football. In some cases, a bundle of rags would be chased after; in others, an animal bladder rabona-ed. Basic match reports appeared in cave illustrations with primitive paints used to scrawl heat maps and pass-completion stats.

I also wonder if you would find the book as funny as I do if you are not an avid Guardian reading snowflaker. Squires is clearly some combination of humanist, socialist, enlightened, liberal democrat. As a humanist, a liberal and perhaps a socialist, he puts the comedic boot into public schools, empire. He tends to express his political values through sarcasm, which itself is expressed as a sucker punch. It is in this way that he brings to light issues of racism, corporate greed and violence. The sarcastic sucker punch often comes after an opening statement, that starts off as a glib remark, characteristic of the kind of thing you might find your squeaky clean broadcasters saying.

International competition is great, as it allows us to reinforce cultural differences and legitimizes xenophobia.

Of the Italy side that won the 1934 World Cup on home soil, with the help of the intimidation of Mussolini, Squires reflects:

Still, you can only beat the unfairly disadvantaged team that’s put in front of you…

He also has a go about football politics: the London-centric FA. He takes the piss out of Jeremy Clarkson, Jeremy Clarkson’s friend David Cameron for pretending to support Aston Villa. Throughout the book he relentlessly brings to light the corruption in the game, dragging FIFA into the spotlight. He attacks military fetishism; poppy-wearing fascism; the careless sacrifice of British soldiers by the military leaders in World War I;

Its a book about football, but in many ways, its also a book about politics and culture, told through the prism of football. Squires uses a play of words, of kind, to remind us of the Daily Mail’s support of fascism in the 1930s, he has Mussolini looking embarrassed about being found with a copy of the paper, claiming that it was a bit too right-wing for his liking. Squires reminds us of how the deterioration of European culture and politics in the 1930s, permeated and provided the context to international football in that decade.

He takes taboos and brings them to life through humour. He asks what it would be like to be alone with Roy Keane on a camping holiday.

In his article on the selection of the striker for Austria’s Wunderteam he has a comic strip set in an Austrian cafe, only he substitutes 1930s Vienna for 21st century Shoreditch. The drawing and characters are brilliant, and the final frame, two fried eggs presented on trowels, with chopsticks to eat them with is just fantastic. At the same time he tells the story, but really in many ways, uses it as an excuse to take the piss out of trendy hipster culture; to tease out the comical side, to caricature.

Squires is also modest. The drawings are great, the book is an incredible work of art, and yet he retains an immense sense of humility.

He manages to weave other cultural references from the last forty years, including the group The Shamen.

He deals intelligently with all angles of the game, using language in such a concise form, using the modern business speak pervading the game.

One of the keys to Squires brilliance is his knowledge and understanding of the lingo deployed across a cross-section of classes, contemporary and historically (young teenagers; hipster cafe owners; Victorians). Not only does he have that knowledge but he is able to use the argot from that culture in a precise and concise way to capture the essence of the habits, quirks, the idiosyncrasies, the affectations, the prejudices. Whilst his writing and strips are concise and to the point, and flow so quickly from one theme to another, they suggest an encyclopaedic and forensic knowledge of football; and an incredible ability to capture and crystallise its essence, in a few choice words that represent particular classes, national personality.

The comic strip for the England v Italy 1934, which you can see here online on Google (scroll down one page), match is a brilliant example of how he takes a story and uses each frame to tell a new kind of joke. There are two things going on, then. The story itself, which is told in a very interesting and factually concise way throughout the strip. And then in each frame, each step in the story is worded in a way that allows Squires to segue way into a joke about something different. For example the first frame makes a joke about the traditional English preparation for a football match involving friend breakfasts and beer; the second frame provides the opportunity to highlight the support for fascism of the Daily Mail (in this way – what I begin to realise and appreciate is that it is not just comedy and laughs that Squires is aiming for – he is also using this as an expression of anger and disgust at certain types of politics – it is a heady combination of comedy and aggression; it is an opportunity to use the book to kick a political enemy in the bollocks); the third a combination of anger and comedy in that it has Mussolini looking rather embarrassed and trying to explain how he has come to be found to be in possession of a copy of the Daily Mail, which he views as too right wing for his own views; the fourth English xenophobia; the fifth back to the traditional backwards English techniques for preparing for a football match; the sixth the kind of pranks and antics that footballers tend to get up to; and seventh and finally, allusion to the terrible state of England side under the management of Steve MacLaren (in fact this last frame is not really a joke at all; instead it is quite depressing – which makes me think that what Squires again, is not always just making jokes; he is more generally pressing emotional buttons – in that for example, if we take the first and fourth frames about pre-match beers and fried breakfasts, he is not just having a laugh, he is also reminiscing, about something about the game that has been lost; it is almost mournful and yet warming too in that it reminds us of a more cosy, in some ways more innocent and less complicated era; in the second he is switching it completely and using the story to give the Daily Mail a deserved kicking; in the third he is making fun of xenophobic attitudes, but again raising questions about the pervasiveness of xenophobia in society and football; and in the fifth about the disgusting antics and pranks that footballers in the 90s were getting up to, its funny but its also disgusting; and then finally in the sixth the dismal feeling that any England supporter felt during the reign of Steve MacLaren. So we go on an emotional rollercoaster including warmth, nostalgia, mourning, aggression, disgust with xenophobia, horror and despondency – and yet these are all only side shows in the story that was England’s 3-2 victory over Italy

The wording of each element of the story, in each frame, deploys different styles, which allow for the digression into the joke. Sometimes the fact is twisted at the end, with something essentially untrue added on which allows for the segue; (for example the bit added on is sometimes expressed as an idea that things were never again as bad, or as violent, or as corrupt after this moment, suggesting that the game had reached a nadir – the joke, of course, being that some event in the future, something that most likely happened in the period that Squires was conscious of as a child or an adult, demonstrated that it clearly wasnt), or the fact is essentially a double entendre true to the story but also hinting at something else, which allows for the joke; sometimes the joke comes in off the back of the fact being an addendum to it;

On the inclusion of Steve MacLaren’s reign as manager of England, Squires unearths past footballing traumas, which are not written completely out of England history, but are largely forgotten in the national consciousness in the national construction of the best moments of England’s international footballing history. In this way, arguably, he presents an emotionally fuller picture of our footballing life and history, its a therapeutic read in some respects.

In one single comic frame he was able to make a joke about young people liking FIFA, making it look as if he was referring to how young people loved the game FIFA, dropping in a comment from a young white kid, imitating black street language, and in the process directing our attention to the fact that the game they were playing on the screen, was not FIFA soccer but rather a game which seemed to involve passing money, in a corrupt deal from one official to another, bringing the joke back round to the original point of the article, about the corruption in FIFA, and that in particular, at its heart, it exists to make money in a corrupt manner for its members.

At the end of his introduction to the book Squires leaves off with ‘I hope you enjoy it. It took me ages.’ Those last four words hints at the enormity of the task for Squires in crafting the flow, pace and humour in the text and the comic strips he presents. In many ways, like Ian Rush, because everything flows so well and produces laugh upon laugh, Squires makes it look easy. It almost certainly wasn’t. But is was well worth the effort.