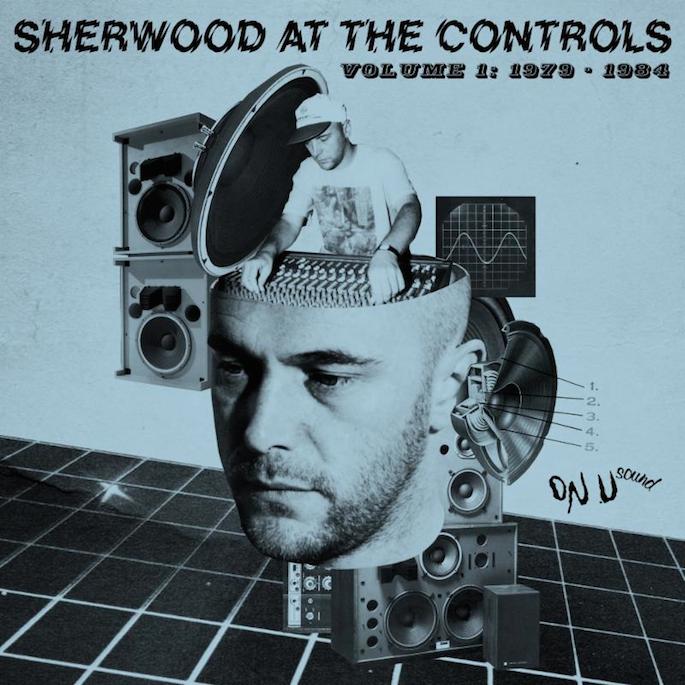

One of my primary musical obsessions, which I have nurtured since my teens in the 80s is the production of Adrian Sherwood – especially those on his label, On-U Sound, and those in his most experimental period, from 1979-1989. Given the opportunity, I will write more about On-U Sound, but aside from giving the world African Head Charge, Dub Syndicate and the New Age Steppers, the label formed the intersection between the London post-punk scene, the Bristol punk-funk scene and Jamaican legends Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and Prince Far I.

‘Sherwood at the Controls’ offers a brief (far too brief) look at this intersection and the magical, inventive, destructive, jarring, sheer mind-fuckery of Sherwood’s early productions. The track-listing includes On-U stalwarts African Head Charge and Prince Far I, alongside an array of early 80s luminaries The Fall, Shreikback and The Slits.

Take, for instance, ‘Mister Linn He Dead’ by early 80’s indie-dance outfit Shreikback. A remix of ‘Hand on my Heart’, Sherwood totally deconstructed the song, breaking it into it’s component parts and creating something utterly new. Utilizing the tricks and techniques he had perfected on his own dub recordings, the drums pan from left to right, by turns drenched in echo and/or reverb. Vocals emerge, distorted and fractured, barely recognisable.

Alternatively, Sherwood’s production on ex-Pop Group singer Mark Stewart’s title track from his 1981 LP ‘Learning to Cope With Cowardice’. The release here is a shorter version than that on the album, released as a flexi-disc for Dutch magazine, Vinyl. Both the original and this version are underpinned by a propulsive dub reggae beat and is accompanied by a range of instruments so processed as to be unrecognisable. The effect is invigorating and bewildering. Mark Stewart himself rides above the fray with almost Dadaist pronouncements; his voice bursting in and out, at times pouring into the red. It sounds like nothing I have ever heard, before or since.

Not every experiment works as well. Sherwood’s deconstruction of Swiss singer, Nadjma’s ‘Some Day My Caliph Will Come’ is so disconnected from its source that the fragments never coalesce into anything more than a collection of its parts, rearranged and repositioned. Maximum Joy’s ‘Let It Take You There’ strikes me as a good, but not great example of post-punk, punk-funk that is far better exemplified elsewhere, not least by Stewart’s Pop Group, New York’s Liquid Liquid or even the Gang of Four.

It is on the On-U mainstays releases that Sherwood’s vision of dub reggae comes clear. Singers and Players, a loose collective of On-U’s Jamaican regulars, not only rivals but exceeds the productions of King Tubby in terms of inventive use of sound and space. ‘Reaching the Bad Man’ from ‘War of Words’ has the late great Bim Sherman riding a rocking bass. Drums pour in, bathed in more echo and reverb than is safe. Guitars, unusually for a reggae track, distort. Synths creep in and out. Waves of sound lurch forward at risk of inducing seasickness, as some other other-worldly sound is poured down. Someone somewhere in the background intones about judgement, as though a street preacher wandered in to condemn all this sonic decadence.

All of the 14 tracks here offer discreet reasons why Sherwood should be listed as one of the world’s most important producers. These early recordings show a wilful exuberance and determination to push the boundaries of several key genres. Sherwood’s early career sparked or influenced a great many musicians and producers that would come to prominence in their own right in the later 80s, or 90s; including Neneh Cherry, Geoff Barrow and the Bristol scene in general, Kevin Martin and Trent Reznor.