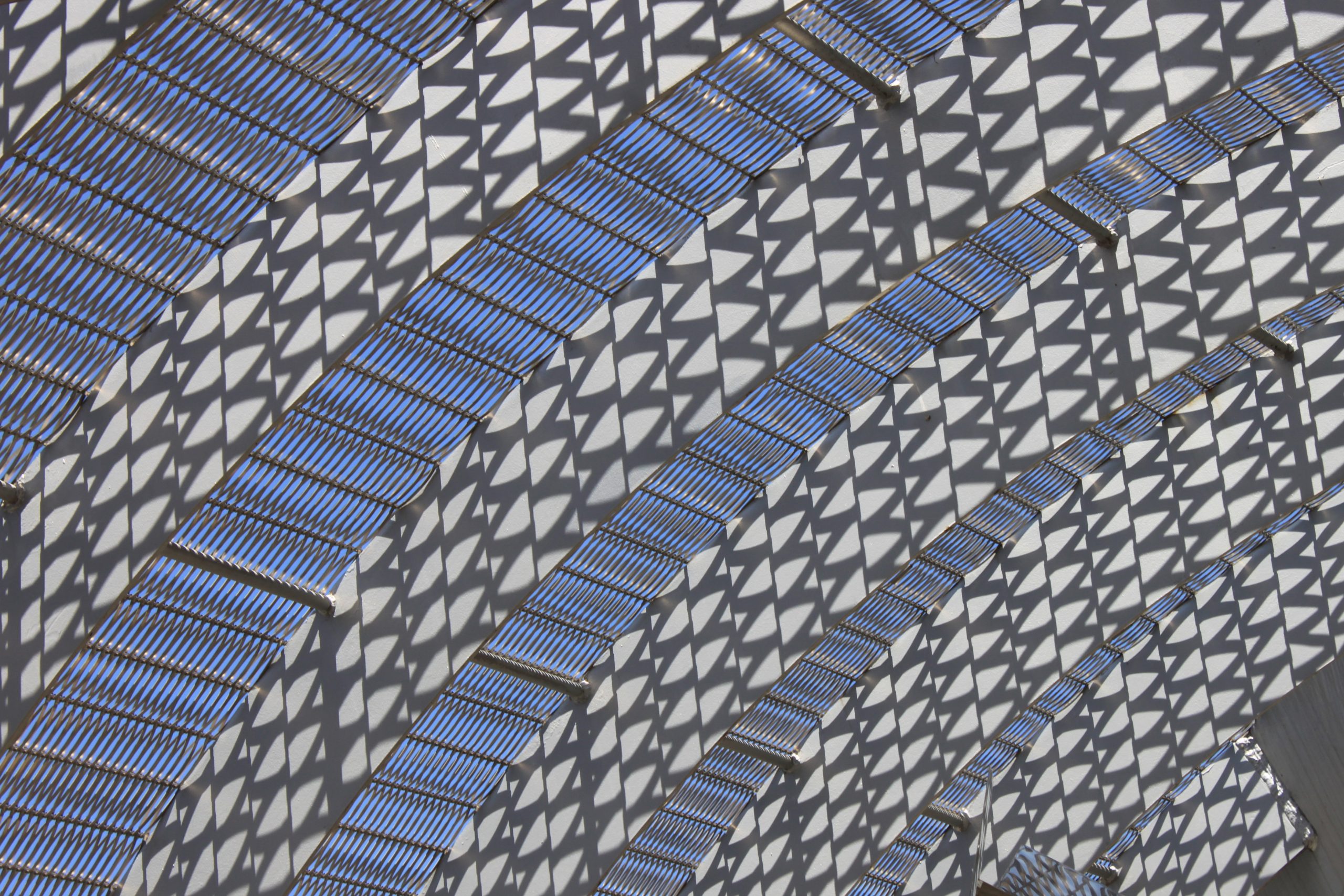

Madrid has a river called El Manzanares, which runs down its western edge, at the foot of its royal palace, which looks over the western plains of Madrid.

In the 1980s Madrid built two busy ring roads either side of the river, making the river a fairly unpleasant place to hang out and live.

But in 2003 Madrid’s right-wing Council decided to bury the ring roads underneath the river. In the space previously occupied by the roads, the council has built footpaths, cycle paths, gardens, fountains, playgrounds and cafes. Its a remarkable development, not least, because the mayor, Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, was from the right-wing part, Partido Popular, and the major beneficiaries have been the working class people that lived in the areas around the river.

The stretch of river developed is known as Madrid Rio.

The work was completed in 2009 and I’ve paid regular visits to the site since.

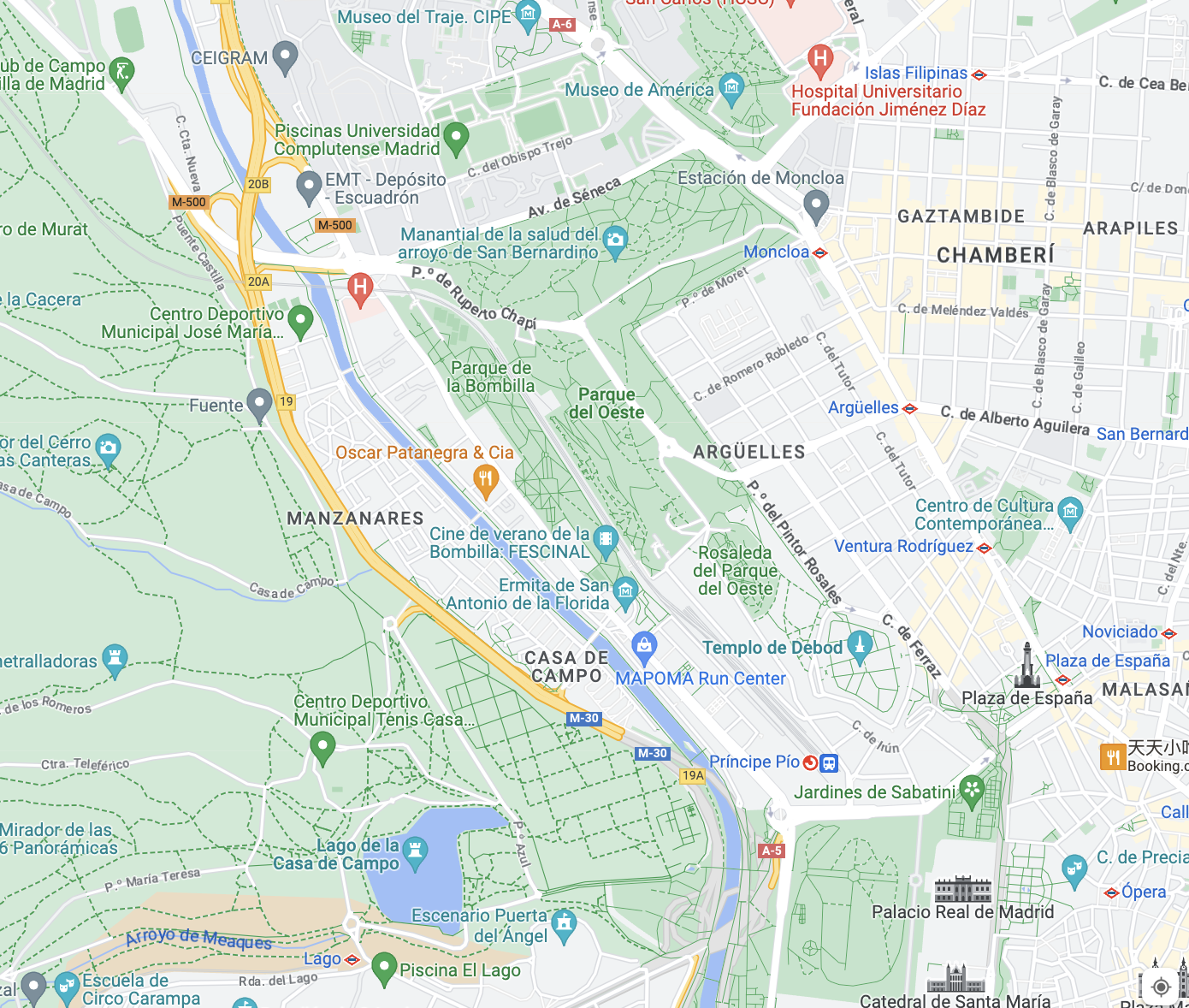

This before and after, gives you an impression of the difference that the development made.

One thing I’ve never done though is walk the full length of the development.

In July 2023 I determined to walk to both the northern and southern extremities of Madrid Rio. I was interested to see the extend of the developmendt and change in environment of the river, beyond the development.

Walking to the Northern Edge of Madrid Rio

I decided to first try and walk to the northern edge of Madrid Rio, starting from the section which runs parallel with Principe Piu, the train station servicing the north-west of Madrid.

On descending to the river I couldn’t help but fall in love. Much of the river was now full of reeds, wild flowers, bushes and trees, which seem to have been allowed to have grown. The effect was to turn the river bed into some kind of glorious tropical jungle garden, off limits to humans, but full of butterflies, insects, butterflies and birds. This appears to be a conscious decision made by the authorities – years ago – photos taken of the river show a flat river bed with a very thin layer of water running across it.

This sort of jungle arrangement is made possible by the fact that the Manzanares is not a big river, especially in summer time, there is not a lot of water flowing through it. The result is that there is plenty of space for plants to take route and grow. Now, in July 2023, the river courses its way left and right, sometimes in multiple channels around the beds of plants and trees that have taken route.

Small herons sit on the borders, taking shade, and occasionally venture into the water to take a bite. Swallow like birds, swoop, dip and dive, suddenly checking their movement to catch an insect unawares. Butterflies tickle the air.

Whilst Madrid Rio sits at the foot of Spain’s Royal Palace, it is not located in the centre of the city. It runs on the western side of the city, and is located in working class districts. The outer borders of the river’s pathways are formed by blocks of residential flats, at the bottom of which there are various shops and workshops.

On a hot July summer’s day, then, with most people at work, the paths along the river feel deserted. You see a few solitary individuals or a couple walking, one of them with a shopping bag in their hands. A scooter rolls down the pavement, there’s the occasional car. An old man is slumbered on a bench in deep sleep. A Vietnamese man plays with his children in a very small rundown play area.

With the exception of the occasional air conditioning system nature provides the backing track. Chirps and cheeps from the birds, the buzzing of the Cicadas, sitting in the pine trees. The occasionally plopping noise made by elusive fish in the river. You feel like you’ve been transported to some kind of mini-Amazon.

Past the bridge, at the legendary Casa Mingo (a 19th Century roast chicken joint) the pathways and playgrounds are strewn with limey yellowy petals. So are the al fresco tables, seats and plates of the Extramaduran cafe, which attracts a few customers.

A flock of goldfinches, as many as one hundred, chatter incessantly, and skip playfully from one tree to another, always staying ten yards in front of me.

There’s street art and graffiti on the walls. A momentary nasal assault, a sewage like smell, penetrates deep inside of the brain. As you walk along the river, northwards, you feel like you’re heading out into some kind of wilderness.

There are, at various points along the river, a barrier arrangement, to stop flooding I imagine, with some sort of Victorian-esque arrangements in the centre.

I come across one of the huge posts of the cable car arrangement that starts on the western side of Madrid, and takes passengers into the centre of the nearby park, Casa de Campo. The wires of the Telesferico only just reach above the top of the trees.

Every now and then, both sides of the river you occasionally bump into one of these Romaneseque concrete poles, which I can only assume, used to hold up a bridge.

The path ambles on towards a large stone arched bridge, called El Puente de los Franceses, used for railway lines. This is the end of the Madrid Rio development. The human hand has not interfered here much. All manner of plants make homes in the paving cracks, amidst the dog shit, litter and against the hum of the hospital building that backs on to the river.

The memory of the Republican government, overthrown by a bloody military coup in the 1930s, is kept alive on benches and lamp posts.

The river continues under a series of motorway bridges as it reaches a major transport intersection on the north-western edge of the city.

I contemplate edging down on to the dry river bed and passing underneath the bridges, but at the first bridge I come I see a sleeping arrangement or dwelling. I hesitate and decide to head back up to the road, which I cross.

I then peer over the edge to see the river heading under a second bridge. Already I can see, underneath the bridge, on either side, several additional dwellings. A man emerges with a plastic washbasin, the contents are poured in the river. Modern day trolls. I dare not pass. I don’t want to invade their privacy or territory.

I wonder if there are other ways of getting back to the river, but I get lost amongst the maze of motorways and footbridges. Venturing further north is another adventure for another day, and probably on bike.

I head back along the river. And find that underneath another one of the bridges, an old steel cage, which in olden times would have been used for storing maintenance equipment, has been repurposed into a micro-shanty town with bits of wood and old doors nailed together. I see no-one.

Further on, back towards the bit of the river near Principe Piu, its clear that more time and effort is put into maintaining the development. There are impressive play areas.

Walking to the Southern Edge of Madrid Rio

At foot of the Royal Palace, the developments around Madrid Rio are at their most grandiose.

El Puente del Rey is a very wide bridge, which heads in the direction of a small lake next to the old royal hunting grounds, turned into a public park by the Republican government of the 1930s, and known as Casa de Campo.

Women (I imagine) hang washing up by the side of the river, goats are grazing, just by El Puente Del Rey in the 1920s

Several policeman on horseback slowly trot across the bridge on this hot summer’s day. They are accompanied by a police car. In the opposite direction, a few groups of wandering tourists.

At this part of the river, the paving and tiling on the surrounding walkways are immaculate, and managed to perfection.

The amount of land either side of the river is so much that there are always several options and levels for walking. You can walk down by the riverside, or up a few levels, where people rollerblade underneath the trees.

Across the river on the banks of well watered green grass, small groups of young women practice dance routines with a medium amount of exertion under the shade of the pine trees.

Solitary individuals sit down and zone in on their screens. The sound of workmen cutting through stone, sears through the air.

The numerous fountains give off a merciful breeze.

Birds cheap, camouflaged cicadas produce a coruscating sound.

Further on I get to another one of the old classic bridges across the river, El Puente de Segovia. Originally, built in 1564, but then dynamited during the civil war in the 1930s, and rebuilt in 1943.

Past the Puente de Segovia and we find a number of more modern, and quite impressive looking bridges.

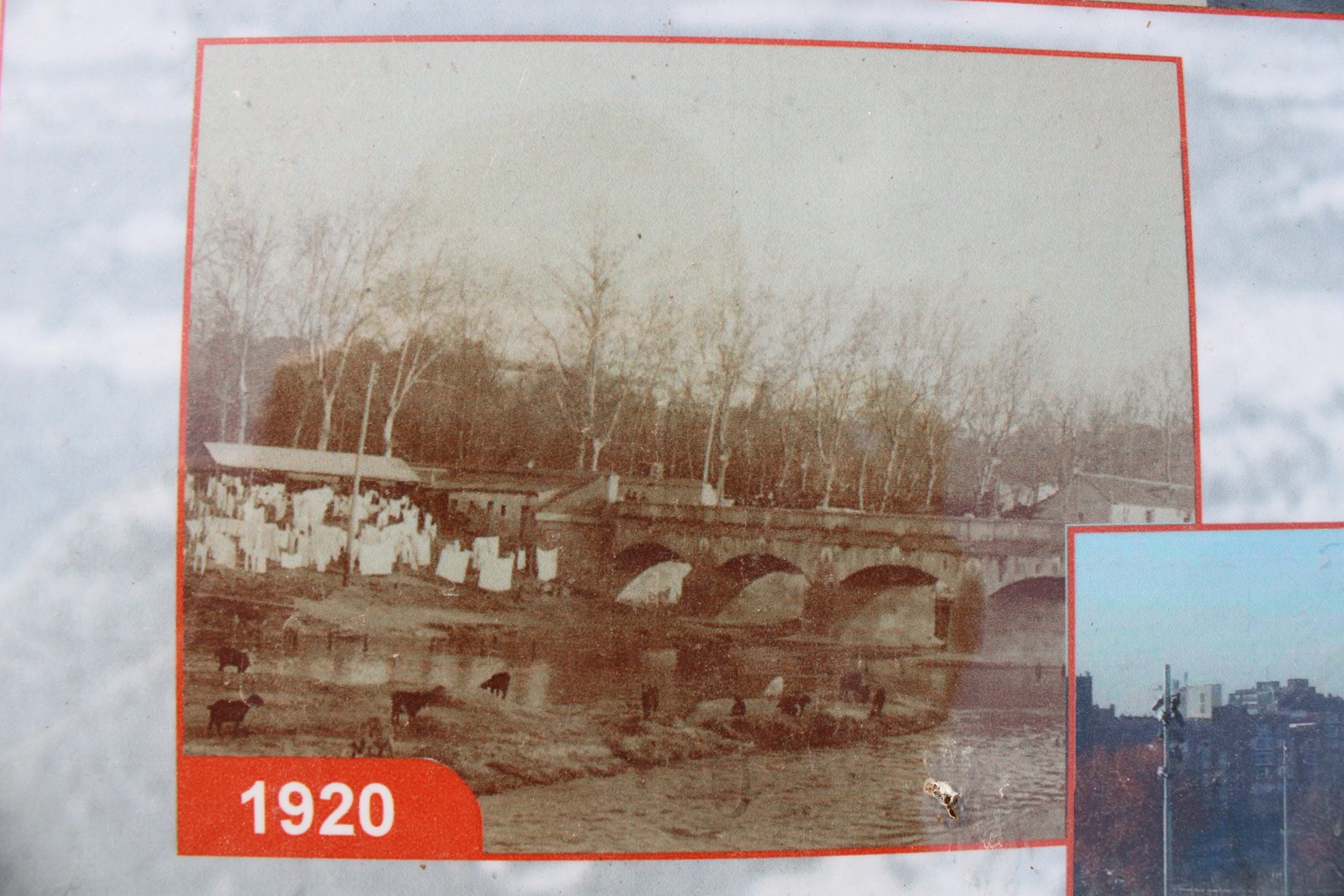

El Puente del Principado de Andorra plays with angles and lines. When the sun shines it adds to the effect. The dark green colours of the bridge blend nicely into the environment.

I walk past the site of the old Atletico de Madrid stadium, which used to be a spectacular site, by the river. Now the area has been prefaced with a grey wall, behind which new blocks of flats are going up. There is a plan to locate a fake beach there.

Then on to one of the most stunning bridges, behind which sits a working-class part of Madrid.

I venture onto the back streets and take some Argentinian empanadas, one spinach and cheese, one spicy chicken and one apple crumble. There’s a south American theme in this part of Madrid. At the foot of the flats, there are small shops. More empanadas for sale, this time Colombian. A Peruvian bar.

The next impressive modern bridge is La Pasarela del Canal, a silvery grey affair, which looks like a cork-screw in action. Again, when the sun shines, the patterned effect is amplified.

Nearby, parakeets and blackbirds munch on unripened figs, growing in the trees.

Children across the river play in the fountains.

Cyclists, skateboarders and scooters make their way.

Sparrows scavenge. Herons fish.

The trees are deadly still, meditating in the dry heat, they might burn tomorrow.

Further east we come to a micro-hipster zone, an extraordinary pair of bridges. They are identical in shape and build, with curving concrete roofs. On the underside of the bridges, on the ceilings, are painted people skateboarding and striking poses.

On one side of this pair of bridges is a contemporary art centre, fashioned out of an old slaughterhouse. It is call La Matadera. On the other, is a modern shopping centre. A famous street artist has painted an extraordinary mural next to the shopping centre.

I walk on still, but its clear that I’m beginning to reach the limits of Madrid Rio. Underneath a non-descript bridge, carrying traffic, I notice a slim guy with his legs stretched out. He looks solemn, a little agitated, he’s listening to French language African music, on what is probably his phone, but which sounds like a transistor radio.

I look behind him. Where the bridge meets the ground there’s a ledge, where someone has constructed some kind of temporary accommodation for themselves. There’s a crate, a mattress and a screen.

Just a few metres on a couple of pigeons are resting on the floor. One, disturbed my present, gets up and walks most gingerly on the one remaining leg, which appears to be a stump.

Shortly, the subterranean roads re-emerge, both sides of the river, still beautiful, but now captive.

The sound of cars is bewildering and dominating.

Only the cicadas can compete with them for noise.

Pedestrians can continue alongside the river on a narrow wooden walkway, squeezed between the river and the ring roads. I hesitate to commit because I’m not sure where it’s going to take me. But curiosity lads me on, and my cat survives.

It takes me into a strange area, dystopian, a park of sorts, set underneath a series of interlaced motorway bridges and old bit of concrete. Some attempt has been made to develop the area. There are a number of plain concrete benches, which look relatively new, scattered about. A few unfortunate souls have to take this route to get their business done. Its not a nice area.

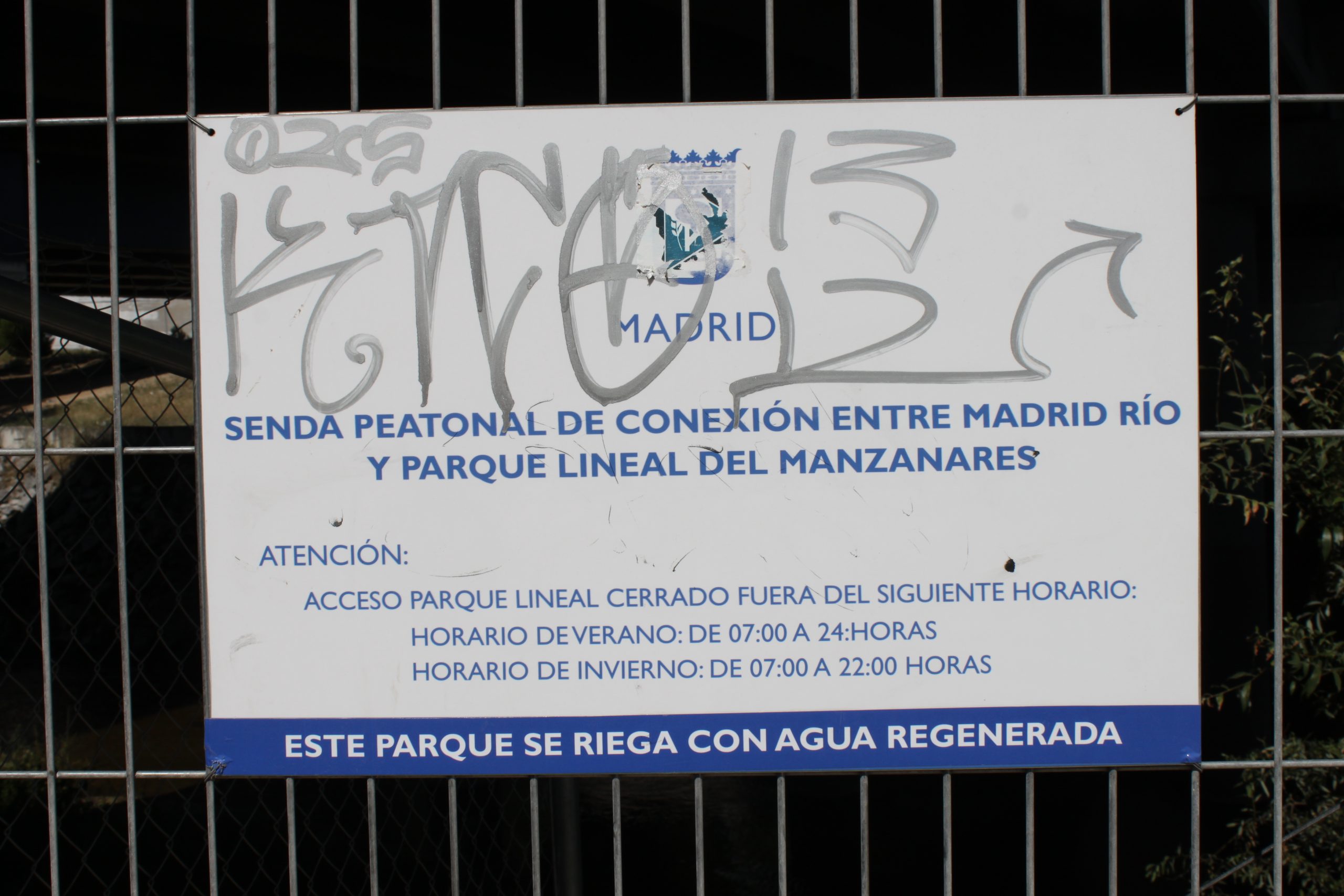

But the path, with time, leads to a park called El Parque Lineal del Rio Manzanares. This turns out to be a well developed park, with quite a few impressive looking sculptures and bits.

There’s a path that borders the river, although separated from it by a small wood. A rabbit or hare runs on 30 metres up from me. It’s behind wobbling from this side to that.

I notice an opening in the wood, and take a path that takes me, for the first time, to very side of the river. This is the first time, on my journey, that I could dip my toes into the river.

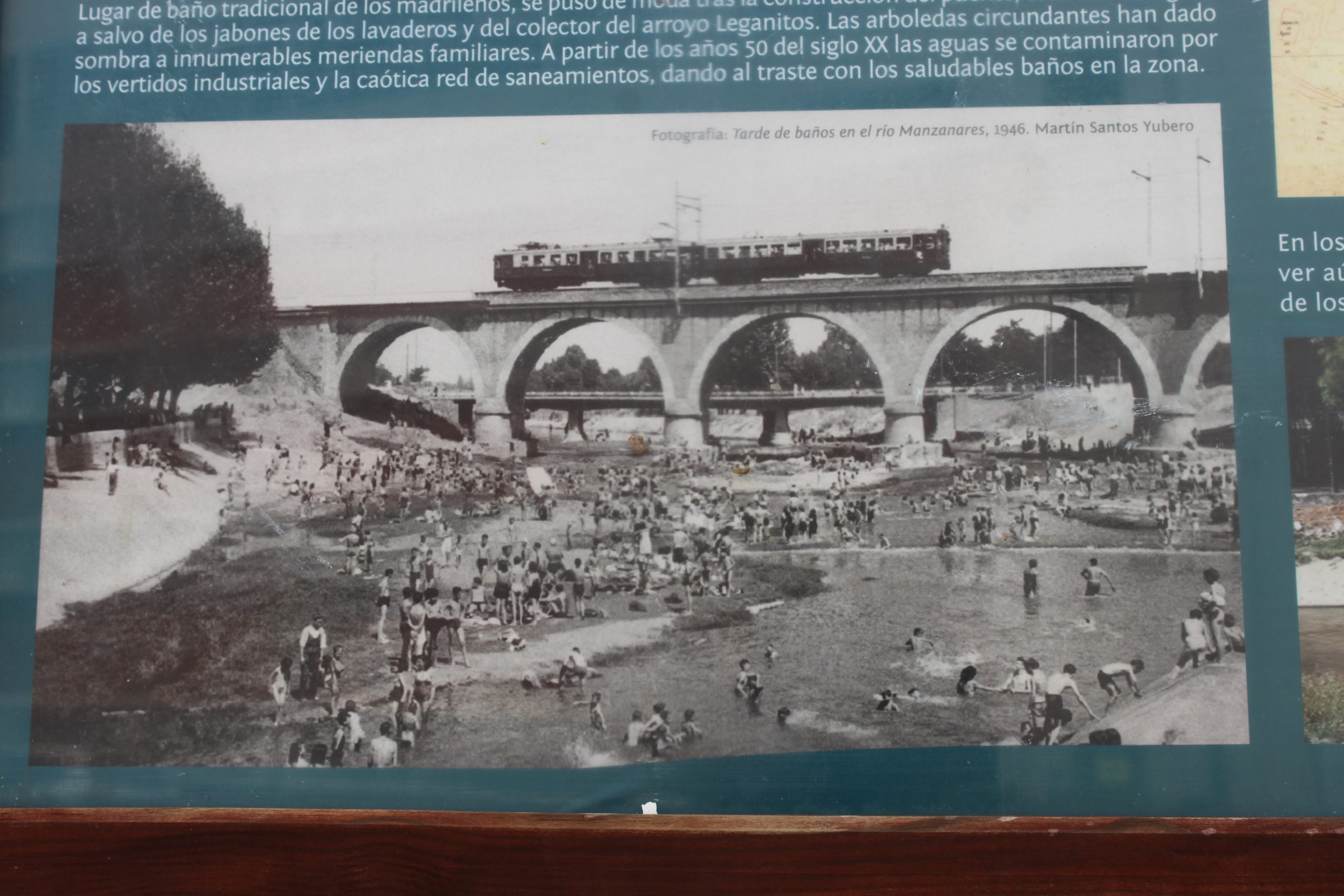

If you could forget that this river was surrounded by cars and motorways and rushing noises and pollution, and if you could ignore the fact that there is a smell of sewage in the air, you could easily feel and think that this was one of the most beautiful places in the world. The river is wide, so shallow, that children could easily play in it, and I hark back to the photos of the river, when they used to do that, and think what a shame that this river isn’t clean enough for them to do it now. They could have hours of fun.

A fish makes a bubbling noise.

In the park, the most impressive monument is a big head with lots of metal lines orbiting it. It is located on a small hill, from which you can get a marvellous view of the city. This is a fitting end point for the end of my excursion. I will surely follow the river on, but next time, on bike.

See also, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://cdn.archilovers.com/projects/301e8280-f014-46a2-a725-d39d524740f2.pdf