Today the cultural folk-devils of 21st Century establishment Britain are Islamofascists, a vile lot, most of whom are in need of a good hug. Twenty years ago though no-one had ever heard of an Islamofascist. In 1994 the enemies of the state were environmentalists, ravers and new age travellers.

Although I’m not sure that new age travellers ever really existed independently of environmentalists and ravers, all three cultures were a response to the cold and dominant politics of the Conservative Party. 1990s Britain was pretty depressed. Thatcher instigated policies, backed up with police violence, that devastated many parts of the country. Once Margaret Thatcher had come to power in 1979, the manufacturing base, under threat from a fast industrialising Asia, was sometimes pushed, sometimes allowed to fall into the sea. All of this was done in favour of edifying foreign financial institutions, who were being welcomed into the City of London by the mid-1980s. Affected communities in the north of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland fell into despair and alcoholism. Some have been comatosed ever since. But Thatcher was happy with the outcome. There was nothing she disliked more than resistant working class types, especially northern ones, personified in her arch-rival, union leader Arthur Scargill. And there was no favour that she’d avoid giving to these communities. In the lead up the 1987 General Election the Tory led government paid for awareness raising television advertisements for employment and training related opportunities for the long-term unemployed, which were aired only in the South East of England.

By the time 1994 had come around, most of Thatcher’s children, reaching their teens and early twenties had never known anything other than a Conservative administration. No matter what young people might have felt about fostering a society and state, which enabled the people to look after and support each other, it seemed the majority of Britons were hell-bent on a more sacrificial version of society. The news headlines ran that the manager of a burger chain, who had employed staff at £1 an hour, was given a £1 million golden handshake on leaving. At the same time several of Margaret Thatcher’s political entourage were involved in the organised sadistic abuse, rape and murder of young boys and girls from Children’s Care homes, Thatcher had played a significant role in stopping any allegations escaping Downing Street. So, for one reason or another, generations of people who had their lives and self-esteem smashed to bits for the edification of the City of London and the establishment, felt helpless to redirect the general nasty direction in which the majority of Brits were taking their country. On December 31st 1993, John Major was preparing to lead his party into their 15th consecutive year of power.

This feeling of helplessness was what spawned the rave movement, environmentalism and the new age traveller. The rave movement, based in the main on free partying, free love and if it had been at all possible, free ecstasy and speed, was an attempt at mass dropping-out. It was about forgetting the world around you and getting lost in a world synthesised by drugs and keyboards. Whilst many who were involved in the movement, would happily admit that once the effect of the drugs had worn off, the love quickly disappeared, the actual experience of participating in the rave scene, taken for what it was, felt like temporary salvation. And it wasn’t just the drugs, it was the feeling that a huge movement of people could organise themselves without depending on the government, police, schools or corporations, that felt so good. The rave scene, at least at the beginning, was a true punk movement, in which venues for raves were found by entrepreneurial sound systems and DJs, where in most cases, the power, music and entrance to the venue were made entirely free. The raves were sometimes organised amongst the ruins of manufacturing Britain, in old warehouses across Britain, and during clement weather in fields and countryside. In many ways rave culture represented children affecting to strike out on their own, pathfinders to a new way of living, even if all they were really doing was running en masse down a cul-de-sac.

Some people were not completely determined to efface the harsh economic and political realities of establishment Britain by getting off their face every weekend. Some, who still had political motivations, but who acknowledged that there was nothing that could be done to budge the general Tory leaning sentiments of the UK, began to focus on local resistance, guessing that a concentration of local energy might be enough to ward the ghosts of the ghoulish John Major off. NIMBYISM (not in my back yard) as a realistic political philosophy began to be adopted and catch on for a number of causes. Furthermore, perhaps as a result of the lack of faith in people, many politically active types began to take an interest in the environment. Environmentalism, and travelling to protest, became a hobby for some, and a way of life for others. The power of the travelling environmentalist and the stubborn NIMBYist were harnessed when the Tories set about a major road plan for the country. In 1992, Twyford Down, an area of chalk downland lying directly to the southeast of Winchester, Hampshire, England, was marked out for a major road. One evening in March, after two environmentalists, who had chosen to camp on the down, were informed about the impending work by a couple of ramblers, they decided to gather support. Enter stage left a ragtag bunch of environmentalists, who quickly won the ire of red top Britain, but the hearts of many locals who shared the same environmental goals but not the life-effacing bravery.

The protestors always lost their battles, but never stopped the war. A year later they gathered at Solsbury Hill, outside Bath, to protest the building of a new dual carriageway.

In 1994 environmentalist activists joined 92 year old Dolly Watson, the last remaining resident in Claremont Road, Leyton, a street earmarked for demolition to make way for the M11. According to Wikipedia:

By 1994, properties scheduled for demolition had been compulsory purchased, and most were made uninhabitable by removing kitchens, bathrooms and staircases. The notable exception was in one small street, Claremont Road, which ran immediately next to the Central line and consequently required every property on it to be demolished. The street was almost completely occupied by protesters except for one original resident who had not taken up the Department for Transport’s offer to move, 92-year old Dolly Watson, who was born in number 32 and had lived there nearly all her life. She became friends with the anti-road protesters, saying “they’re not dirty hippy squatters, they’re the grandchildren I never had.” The protesters named a watchtower, built from scaffold poles, after her. A vibrant and harmonious community sprung up on the road, which even won the begrudging respect of the authorities. The houses were painted with extravagant designs, both internally and externally, and sculptures erected in the road; the road became an artistic spectacle that one said “had to be seen to be believed”.

Added to all of this was a new media interest in traveller communities, with a special focus on the hatred that others had for the travellers. The media began to talk about the emergence of New Age Travellers. No-one has ever really presented very good evidence to suggest that New Age Travellers wasn’t just a collective term to refer to itinerant ravers and environmentalists, part of an attempt to encourage a level of hatred for environmentalists and ravers that is sometime meted out to travelling Roma Gypsy communities. The fact is though that many of the ravers and protestors had a house to stay, they just chose to spend a great deal of their time out of it, like a businessman or government minister. They chose to spend much of their life dedicated to itinerant hedonistic and environmentalist pursuits, which meant they spent a good deal of their time under canvas, and whatever other forms of shelter serendipity, industrial decline and mother nature might provide.

Whatever the truth and make-up of these constituent groups, what is clear is that by 1994, they were being presented as ante-heroes and villains for papers, looking to stir a bit of shit, and prop up the Conservatives. The Conservative political establishment was determined to vilify and crush these groups, hoping to unify and strengthen their vote in the process. “New age traveller?” posed John Major to the 1992 Conservative conference, “Not in this age. Not in any age.” The genocidal undertones of Major were played out through the violence of the privacy security forces towards environmentalists. According to John Mann MP, one member of the security force had, on Twyford Down, strangled a protestor to the point of unconsciousness, leaving her prostrate for thirty-minutes, and seeking no medical attention for her. The raves and parties that had been set up by the travellers, promoters and DJs, which had attracted such massive following from young people and drop-outs alike, had seen a kind of pop-fascist backlash. Jim Bowen, of Bullseye fame, was to announce to Eleanor Oldroyd, on the radio, that he’d disown his children if they were to join in such protests. This was all going to plan, and laid the groundwork for John Major’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which was designed to stop such things as raves and settlements of travellers. According to Wikipedia:

The Criminal Justice Act included sections against disruptive trespass, squatting and unauthorised camping which made life increasingly difficult for travellers, and many left Britain for Ireland and mainland Europe, particularly Spain.

So 1994 saw a clash of cultures. On the one hand there was a group of drop-outs and young people, who having the time and space to look at the bigger picture, decided to choose hedonism and poverty over full-time work, environment at the cost of economic enrichment, and travel over being domiciled. On the other hand there was John Major and his establishment bunnies, who saw the whole episode as an opportunity to galvanise support, through creating folk-devils out of these drop-outs, out of what was in all honesty, a relatively powerless and passive minority.

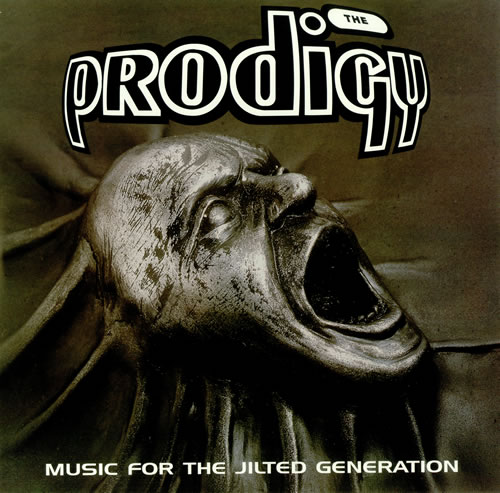

And it was against all this that Prodigy released and entitled their groundbreaking album, of punky hard rock beats, Music For a Jilted Generation, in July 1994. The front cover of Music for a Jilted Generation had a face which was screaming, seemingly suffocated by a metallic film that it was straining to pierce, a fitting metaphor for the disillusioned romantics of Thatcher’s Britain.

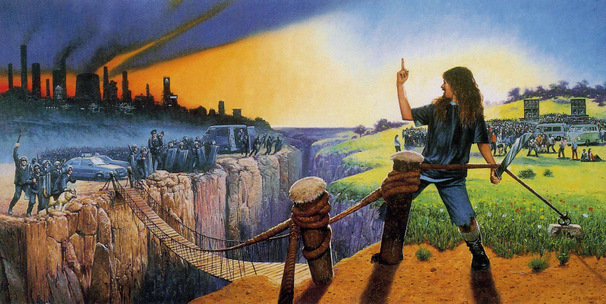

On the inside cover there was a drawing of some festival goers raving on top of a verdant hilltop, where mother nature, amplifiers and turntables appeared to live in sweet harmony. On the otherside of a canyon, an army of military police stood on the perimeter of an industrial town under satanic black clouds, looked over with menacing intent. One of the ravers, a skinny man, in loose t-shirt and jeans, flicks them the finger, and cuts the rope to a precarious draw bridge connecting the two sides.

The Prodigy, however, are no hippies. This was evidenced a few years after Music For A Jilted Generation, when they released a track, violent in sound and misogynistic in nature. Smack My Bitch Up was an intimidating paen to the battery of women, in effect, even if the band would argue not in design. Such a song is irreconcilable with environmentalism and the free love of rave culture. Given Prodigy’s lack of hippy credentials, it leaves one to conclude that, arguably, the significance of the verdant hilltop lies not to much in that it’s a metaphor for eulogising mother nature, but rather that its a metaphor for the market place through which the Prodigy were able to build up a fan base. The fear of the police is not so much for encroaching urbanisation, but rather for the destruction of that market place, upon which was based the cultural milieu, out of which the band’s success grew.

Of course anyone who has the message Smack My Bitch Up ringing through their head everyday is probably struggling with unresolved anger, a lack of success in developing emotional relationships with women, and a lack of success in attracting healthy women. Such emotional dysfunction, was also manifest, nihilistically rather than misogynistically, in No Good the hit single to Music For A Jilted Generation. No Good as intense as you like, uptight, and a dance floor regular throughout the 1990s, repeated “You’re no good for me, I don’t need nobody, don’t need no-one, that’s no good for me”. The song then rockets off, as if a troubled man is walking away from his girlfriend in a strop, firing off from planet earth. The video shows a number of gormless ravers and narcissists, entranced, in torpor, in slow-mo, in a dingy underground bunker. Of course, songs characterising disconnection and disaffection are a feature of any young adult’s life. But somehow, at the time it felt like the nastiness of the Thatcher, the greyness of John Major, the dominance of capitalism over the environment, the poverty and distress and violence, had caused an insufferable amount of alienation in the 1990s. Like the people in the Prodigy’s video, we all felt so atomised. Emotional connection and love, without drugs, just wasn’t possible anymore. We all wanted to hit out, but knew that if we did we’d end up strangled like the woman on Twyford Down. So we admired the environmentalists from a distance, packed our bags and went off to university, where we kicked about wildly, in thin air, on the dance floor. People were feeling pretty fucked up, and the Prodigy, like a Saatchi and Saatchi advertising campaign, like Mike Leigh’s Naked, captured it perfectly.