The Berlin Wall was the physical and iconic epicentre of the cold war between the Soviet Union and the United States during the latter half of the twentieth century. The history of the wall started with the ending of the Second World War during which time the administration of Germany was divided between France, United States, United Kingdom and the Soviet Union. The bits administered by France, the United States and the United Kingdom were amalgamated to form West Germany. The bit administered by the Soviet Union was turned into East Germany. The administration of the old German capital, Berlin, physically located in the bit administered by the Soviet Union, was also split between the four countries. Again the areas administered by France, the United Kingdom and the United States were amalgamated to form West Berlin. The bit administered by the Soviet Union, East Berlin, came to be a part of East Germany. In effect West Berlin ended up being an enclave of West Germany situated in East Germany.

In 1948 the Soviet Union blockaded West Berlin. France, the United Kingdom and the United States responded by airlifting resources into Berlin. In 1961 the Soviet Union controlled East German government built a wall around West Berlin, to stem the flow of East Germans who preferred the life of West Berliners. The wall would come to be known as ‘the Berlin wall’. After the building of the wall East Germans were effectively imprisoned in East Germany. East Germans who tried to cross the wall were shot dead for their efforts, although some managed to evade the bullets and became overnight television set heroes in the western world. The wall also effectively imprisoned West Berliners in West Berlin.

In 1989, in East Germany, the political will for maintaining the wall, which had been standing for almost 30 years, started to crumble and Berliners started to chip away and destroy the wall, in full vision of armed East German border guards. The wall was coming down. In the years that followed the East German communist state agreed to the idea of East Germany being absorbed into West Germany’s democratic political state.

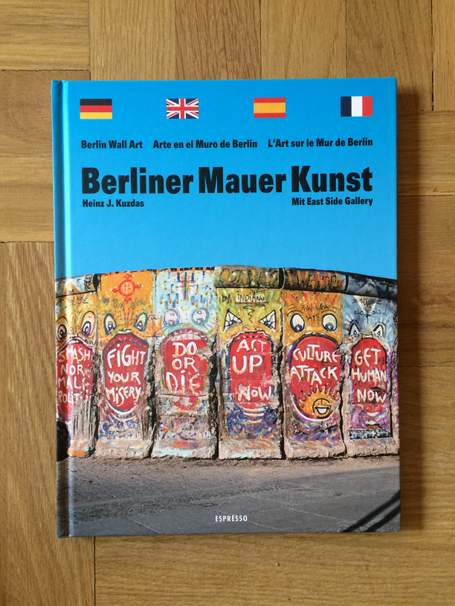

During its thirty years of existence the side of the wall facing West Berlin was subject to a great deal of graffiti and artwork. In the last seven years of the wall’s existence a West Berliner called Heinz J Kuzdas took up the vocation of photographing the graffiti and artwork on the wall. In 1996, seven years after the wall was bought down Kudzas published a collection of his photographs. Michael Nungesser provided text and commentary to the book.

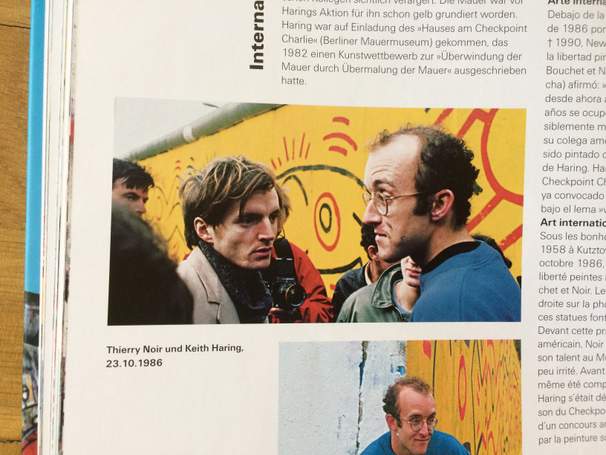

The book is very much focused on the period between 1982 and 1989. Nungesser asserts that for the first twenty years of its life the wall was not as colourful and did not have as many pieces of art, although the book provides no before and afters to illustrate and evidence Nungesser’s assertion. Neither does Nungesser attempt to answer the question of why an artistic explosion occurred as of 1982, the year Heinz J Kuzdas decided to take up documenting wall. Nungesser provokes our curiosity further by identifying two painters Thierry Noir and Christoph Buchet, both from France, as being key to the artistic transformation of the wall. Why did it take two French artists, rather than two German ones, to precipitate this change? Nungesser does not attempt to address this question.

Nungesser is guilty of hyperbole and exaggeration in relation to his views of both the significance of the covering of the western face of the wall in graffiti and art; and of the wall itself. Nungesser called the wall a symbol of political failure, whereas in actual fact the wall was a symbol of the political success of the Soviet Union in carving out a state in Germany. It was the dismantling of the wall in 1989 that symbolised failure. Nungesser eulogised the art and graffiti plastered on to the wall. He wrote that ‘art challenged concrete and art won’ as if the scribbles placed on the wall bore a weight or influence that eventually led to the wall’s collapse. Nungesser wasn’t the only one asserting this, he points out that in 1982 a wall art competition was held in West Berlin, entitled ‘Overcoming the wall through art’. In all seriousness, at no point did art beat or overcome the wall, art was applied to concrete and the concrete stood strong. Lovers of protest art often proclaim that somehow street art unleashes some mystical communal force for the good that will eventually be the undoing of oppressive forces. For example, system-busting properties have been ascribed to contemporary street art in London. It has been suggested that street art in London transgresses the dominance of capitalistic marketing and communications in public space. It’s all nonsense. In the case of the contemporary London street art scene, the reality is that street art is usually an extension of commercially driven interests. Unable to afford legitimate spaces to display their art and advertisement, artists and traders turn to illegitimate ones, i.e. walls or trains, instead. In the case of Nungesser his notion that art overcomes the wall is perhaps the wishful thinking of someone who has a chip on his shoulder about the Soviet communist regime (Nungesser would know better than me about this).

Nungesser also said that the art violated the border with border-obliterating messages. Again this is nonsense. No message ever obliterated a border. Furthermore you don’t violate a border by writing a message expressing your dislike of a wall on the safe side of the wall, the side that those who had constructed the wall could not possibly see. You violate a border by crossing it against the wishes of people who are willing to shoot you dead for trying, which is what hundreds of people from East Germany actually did.

Nungesser tells us that the wall stood 4 metres inside the GDR territory, which meant that the wall painters from the west were technically in East Germany when they did their painting. Nungesser also makes reference to Wall Street Gallery, run by German sculptor Peter Unsicker, which was said to be located on a small street that ran parallel to the wall, half of which was said to sit within East Germany. All of this deserved a lot more explanation and consideration. Why was the wall positioned inside the GDR territory rather than on the edge of it? And if the wall was positioned on the inside why did East German authorities not do anything about the art and graffiti being deposited on it? Although Nungesser intrigued with his comments about the wall lying inside East German territory, the validity of this claim was bought into question elsewhere in the book where it was suggested that much of the artwork had to be plastered on to the wall quickly and under cover of darkness, because West German authorities did not approve. But what did it matter what the West German authorities thought if they had no jurisdiction in the area of the wall?

What is clear is that the art on the wall served the purpose of reminding West Berliners of the need to continue to resist the idea of the wall, whether out of a dream for a unified Germany or for the dream of a unified democratic liberal Germany. Nungesser commented on how the artistic themes deposited on the wall, including zippers, holes, door, ladders and stairs spoke of the hope of overcoming the wall. Other pieces expressed a frustration and anger with the wall. These pieces were not optimistic fantasies about transcending or breeching the wall but rather fury and anger for the reality of the wall, which seemed to rebound back at West Berliners manifesting in resentment. Nungesser and Kudzas draw our attention to French artist Nora Aurienne who painted objects thrown up against the wall bouncing off and breaking up as a result of the impact.

What the author of the book does try to get at, which may be true, is that the infusion of colour, chaos and madness on the otherwise grey concrete allowed west Berliners the opportunity to turn the thing that had been built to oppress, suppress and contain them, into a toy, into something which they could use to amuse themselves. This was not art winning though, as the author suggests, but rather Berliners finding a way of deluding and amusing themselves, using art as a smokescreen to help them forget about the unpleasantness and hostility being communicated and imposed on them on a daily basis. In a way it was like taking drugs, something to take your mind off the banal horror facing you. Perhaps it was a way of mocking the East German state.

During the period of Kuzdas’ photography Nungesser implies that the increasing amount of art work placed upon the wall, and the increasing interest of the media in it meant the art was becoming of more interest than the social, emotional and physical significance of it. In this way the art served to distract the wider media and perhaps West Berliners from the actual political reality, and in so doing sedated any desire for change. Nungesser pointed out that in late 1986 a collective of former East Germans angry at this development drew a very long white line through all the art on the wall from Mairannenplatz in Kreuzberg to Potsdamer Platz. Their aim was to stop the western press and Berliners from sleepwalking into an acceptance of the wall, to give them a slap in the face and awaken a sense of resistance in them. The wall exists and your focus on this art is self-denial said the artists.

Nungesser claims that the Berlin wall represented a unique collective artwork. This is not so, the wall was subject to all kinds of inscribing and imagery but none of this was the consequence of a co-ordinated collective attempt to create ‘a work’. And if it was not a collective artwork then it was not a unique one. Neither can any claim to the art on the wall being unique stand up to critical appraisal. Whilst Berlin was a city, which in its time experienced a unique physical division, and the wall played a part in that, the uniqueness did not stretch to the art on the wall. The art on the Berlin wall was like the art on many walls in many streets in many cities: subversive, throwaway and egoistic but not unique.

The art on the Berlin wall was said to have changed from day to day, it was sometimes displaced, sometimes modified, which is pretty standard for any wall or space subject to the whims and fancies of street artists and scribblers.

And what about the art displayed in the book?

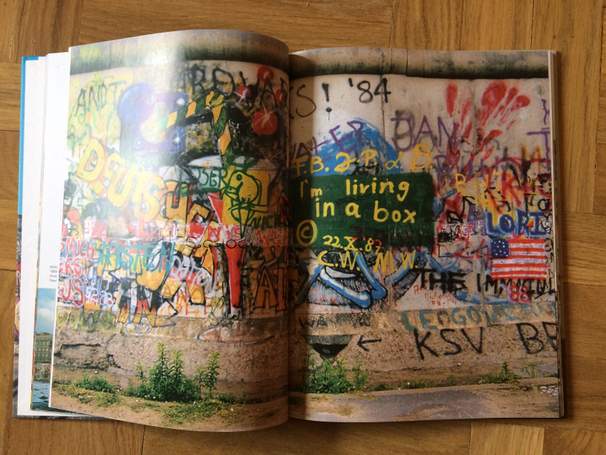

Well the photographs are usually pretty simple captures of different art works, Kudzas in this sense does not appear to be a professional photographer, but rather an amateur collector who is happy enough to snap away on a week to week basis. The actual artworks have little artistic merit. Perhaps the greatest value from the collection is the way in which it helps us to understand the different ways in which the surface of the wall was used to on the one hand distract Berliners from the everyday horror of the wall but on the other to bring that same horror back into their consciousness, to resuscitate the will to fight for a wall-less Berlin. As an aside there’s a photo of a green square painted on to a segment of the wall, with the comment ‘I’m living in a box’ and the date 22.10.87 painted underneath, which makes me think that this is a double entendre, relating to both west Berlin but also to the pop single of the same name released by the band of the same name, which got to number 4 in the German charts in 1987.

What really draws a reader to a book like this is, I would argue, is the opportunity to reminisce about the time of the Berlin wall, to get a sense of what it felt to live at the epicentre of the cold war. To many liberal minded people the story of the Berlin wall is like a fairy tail, a story where good people were living under the gaze of a villain, but where everything was eventually resolved for the good. People want to hear that story played back to them, they already know it, but like all good fairy stories, they want to hear it again. The book doesn’t really achieve this though. Instead it focuses more on what was inscribed on the wall. However to the extent that someone with an interest in the role of art in life would be interested in the book then it would be to understand whom the key protagonists were, what their motivations were and what kind of battles took place over what should go on the wall. Admittedly this book does pay some attention to these issues by alluding to the way in which the art on the wall served to desensitize Berliners from the hostility of the wall, to express frustration to the wall and to awaken them to a political desire to destroy the wall. The book also has a very good photo of what seems like a confrontation between Thierry Noir who painted a set of ‘statues of liberty’ on several slabs of the wall, only to find that some time after an American artist called Keith Haring had incorporated the statues into one of his own works. According to Nungesser Haring after the incorporation claimed that Noir’s work had become part of his, Noir was apparently unhappy with that. The photograph captures what seems to be Noir’s sense of entitlement and ire perfectly, but it does raise a question as to where Noir had gotten the notion that somehow he owned the rights to the works that he had in any case painted illegally on to the wall. However the book does not provide even a basic understanding of who painted on the wall, why they felt motivated to do so, the key challenges they had to overcome and how they overcame them. Nor does it explore West Berliners reaction to so much artwork and scrawl being placed on the wall, and what it felt like to see the wall fall into the informal ownership of those who felt they had something to shout.

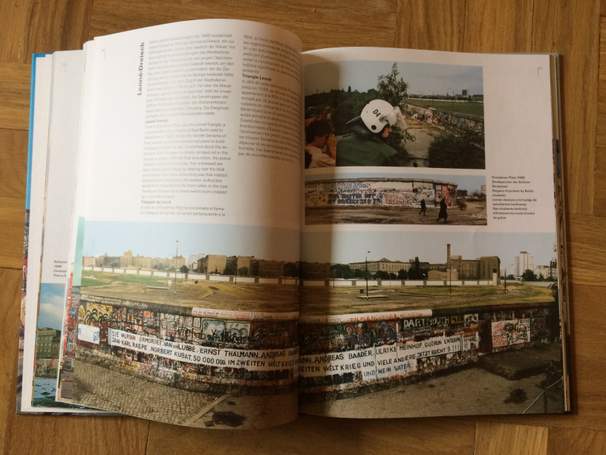

There was one photograph in particular, which was particularly striking, an aerial one. It showed the art and scrawl on the western face of the wall, the lawns of the no-man’s land of some one hundred metres behind the wall, in which the East German border guards stationed in their lookout towers twitched for would-be emigrants, and then the rather drab light brown/grey concrete facades of eastern Berlin behind that. Looking at this photograph really prompted me to wonder whether the East Germans who peered towards the east facing side of the western wall could have possibly known or imagined the mayhem and chaos inscribed on to the western facing side. Did East Germans have any sense of the noisy unauthorised discussion that Berliners were having with each other and the level of self-analysis detailed in that discussion? If they did what did it make East Germans think of a ‘western life’?

Nungesser points out at the end that with the deconstruction of the wall, many of the segments were removed and sold to different buyers around the world as souvenirs. This fact, incidentally, is dramatized rather nicely in the German television series Heimat 3, directed by Edgar Reitz, which chronicled the period of history in Germany between 1989 and 2000. Meanwhile Nungesser points out that the wall was dismantled at such a pace that in the decade that followed the wall coming down, the mayor of Berlin decided to mark the position of the wall with a red metallic strip to help tourists, desperate to see where the wall had actually stood.

Nungesser in his foreword of sorts said he wouldn’t miss the wall, but would miss some of the art on it. In my opinion neither the wall, and judging by Kudzas’s photography, neither the art on it are worth missing. It’s the story of the wall that’s important and Kudzas’ photography combined with Nungesser’s accompanying narrative provides a very small contribution to that story.

Berliner Mauer Kunst Mit East Side Gallery

Photography by Heinz J. Kudzas

Text: Michael Nungesser

Publisher: Espresso

Jennifer Mundy (no date) Lost Art: Keith Haring. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/g/graffiti-art/lost-art-keith-haring