Release date: May 19

This could end up being long, so let me cut to the chase right now. This album is awesome and absolutely worth picking up (you should do so right now).

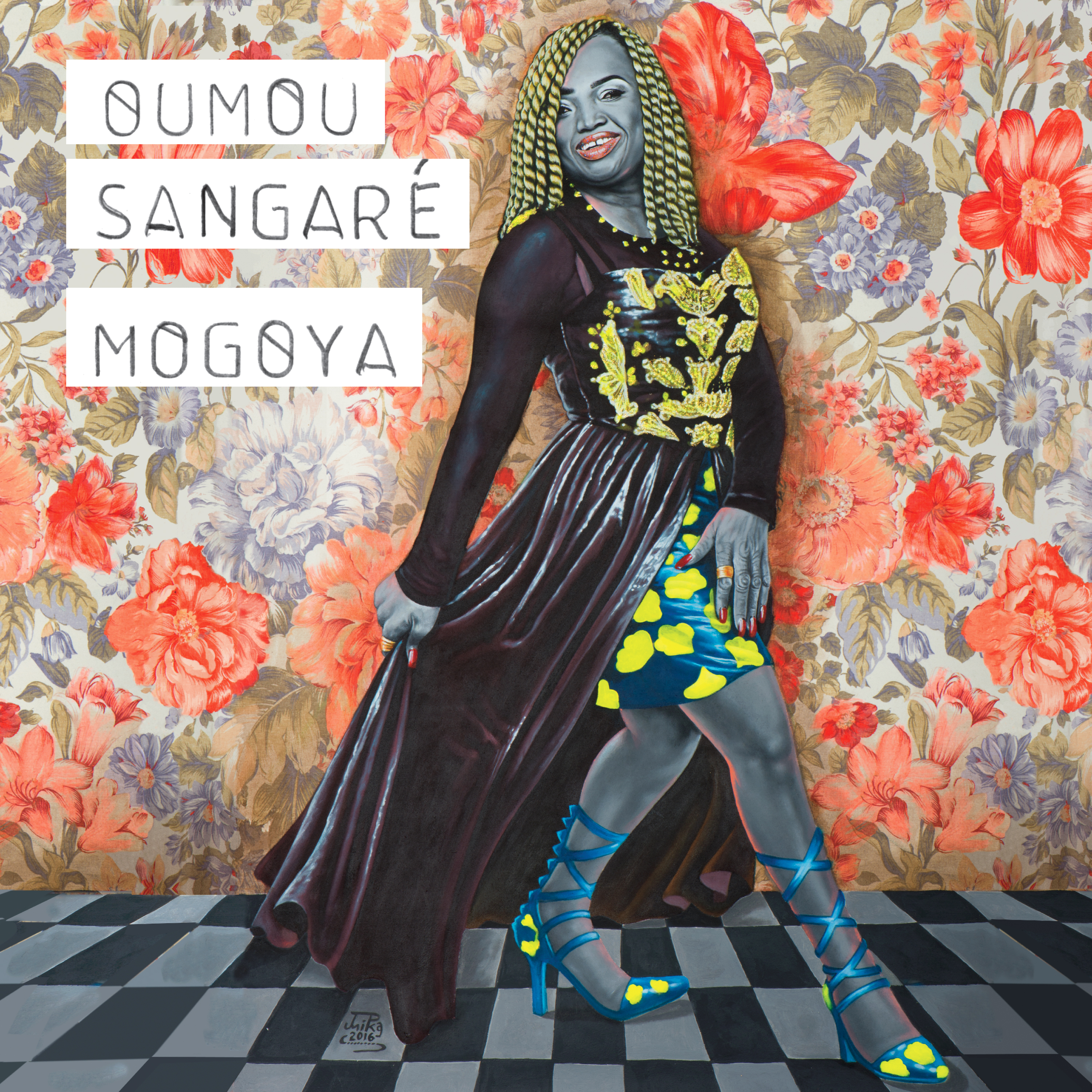

I was nervous playing this album for the first time. The great Malian singer Oumou Sangare had moved from the safe pair of hands that was World Circuit (read: musically conservative but never less than total quality) to Parisian upstart label No Format. Admittedly, the latter has been around a while and has won awards as a label to watch and in preparing for this review I poked around their website – give them their due, good work all ‘round. Nonetheless, there are good reasons to be wary when people try to fiddle around with what is often termed ‘world’ music. Attempts to update the music or bring it into line with European tastes can easily backfire and water down what was distinctive.

The single, Yere Faga, that was released from Mogoya in January was awesome, but, if I am honest, worrying. Compare it to Sangare’s classic work, perhaps Ah Ndiya from her breakthrough album Mossoulou (recently reissued by World Circuit), and the two songs are stridently different. Ah Ndiya focuses on the interplay between Sangare’s powerhouse vocals and the playful plucking of the ngoni, whereas Yere Faga is dominated by Tony Allen’s excellent drumming and has a New Wave air. It is as dislocated from its source as Hector Zazou’s groundbreaking deconstructions of African music with Bony Bikaye and CY1. The bass reminds weirdly me of The Police (I can’t place how) and the guitars and synths recall Talking Heads. All the same, Oumou Sangare rides it perfectly and, despite the song lacking anything that could be described as an obvious structure, it builds and creates a foreboding mood suitable for its consideration of suicide.

But I was worried. Sure, Yere Faga was great – but what did it mean for the album? Was it going to follow Zazou and be interesting and admirable but perhaps not fun? Worse yet, was it to slip into an asinine, neutered Euro-African fusion? Either route was possible. Could it get the balance right?

I needn’t have worried. The album opens with Bena Bena, whisking us back to Mali and showcases why this West-African nation is such a musical powerhouse. The structures, the instruments, the intricate ngoni and kora playing are still present and remain a key part of what makes Oumou Sangare so distinctive. Driving, danceable, playful, uplifting and yet capable of such depth and seriousness, this is transporting. While the principal components remain largely traditional and instantly recognisable, it is in the details that the modern production, provided by French outfit A.l.b.e.r.t., can be seen. On Bena Bena, a zither (or what sounds like one) slides into view elevating an already captivating tune into something else.

It is these details, and the fact that they remain details and not the whole, that gives Mogoya an edge and keep it from suffering in the way that Amadou & Mariam’s albums did in the hands of Manu Chao or Damon Albarn. It is not that those albums are bad so much, but that something is lost in the distance. In shortening the distance between Mali and Europe, the effort is made to make Mali palatable. But being palatable was never the problem.

I suppose there is a sense in which the distance is difficult. When I listen to Malian music, or anything sufficiently distinct from the landscape in which I am familiar with, I am struck by my ignorance of things. What is that instrument? What can it do? Is it being played well or badly? What kind of music is it anyway? (To call it world music is beyond insulting if you mean anything more than where you might find it in HMV.) I guess most importantly, what the hell is she singing about?

We can get caught up in these questions and sadly, I suppose it is true to say that for most people they are sufficient to ensure that the music remains niche or perhaps occasional. Malian music for the Malians; Anglo music for the Anglos…

Except, no, this is bullshit. Even a first listen to this album will reveal all the important things we listen to records for: virtuoso singers and players, hooks, compelling rhythms that make us move – whether up or down, did I mention hooks? A second, third or fourth listen reveals more and more. The intricacies of the stringed instruments (I am never quite sure which is which), the persistent, fidgety rhythms, which I imagine reflect the sounds of life in Mali (in the same way that I imagine that motown and MC5 reflect the sounds of industrial Detroit), and Oumou Sangare’s vocals that pour through me and make me want to scream and shout and dance and laugh and cry.

Listen to any of the tracks of the new album and there will be something there; something new, something different. Fadjamou has the fiercest Afrobeat rhythm, courtesy again of Tony Allen. There is an organ part that begins like it is offering a simple solo until it tilts towards the psychedelic. Tracks 5 and 6 Kamelemba and Djoukourou are dancefloor gold – traditional dance rhythms, where the distinctive Malian-ness is still primary, but where the embellishments suit and contribute perfectly to accentuate the hooks and dynamics of the songs. Mali Niale and the title track bring the energy down beautifully and offer perfect counterparts to their dancier neighbours. The album is timed and paced to perfection. In all, distinctive elements are used sensitively and thoughtfully. The songs are not simply blended in their components (African or European), but carefully added where they will work to maximum effectiveness.

What I have barely spoken about at all is Sangare herself. Alongside being one of Mali’s national treasures, she runs a hotel, has established a line in automobile manufacture, sells a popular brand of rice and still finds time to work for the UN. If you imagine the energy, power and determination to make these things happen in a society that remains broadly patriarchal, you might be able to anticipate the forcefulness of Sangare’s vocals. She is a strong vocalist, but she is no belter in the simple sense of the word – she maintains the subtleties and softer elements of the songs to make them work as documents of a life lived.

So, to conclude, what do I want to say about this record? It gets the balance right. It is everything you want a record to be, regardless of genre, background, or anything else. If there is any justice in the world, this will be a contender for album of the year.

2 thoughts on “Oumou Sangare Gets The Balance Right”