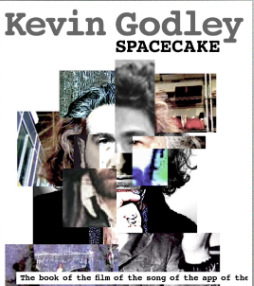

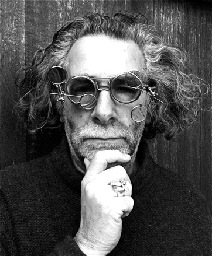

Kevin Godley’s long and illustrious career in music is something to be marvelled at. From his early success as a founding member of the successful rock band 10cc, and duo Godley and Creme, to becoming one of the most sought after and innovative music video directors of his generation, he has well and truly done it all and worked with some of the biggest names in music in the process. Spacecake is a truly entertaining and honest account of one mans experience of the sleazy world of Rock & Roll and the heights of musical success.

I just finished the book, I found it to be very funny which I didn’t expect. Was that a conscious effort to try and make it that way?

Kevin: When I first started writing it it naturally seemed to fall out like that. I have a tendency to look at life as a series of absurdities. So it kind of wrote itself in that respect.

The book has been described as part-autobiography / part-creative manual. What was the initial idea?

Kevin: Well, I’d never really considered writing a book before, but the more I thought about it the more I thought it’d be a good challenge. The thing that was mostly interesting was the fact that it could be an interactive experience, that I didn’t have to rely on the written word for people to be entertained by the book. They can actually see things and listen to things while they are reading. It’s more of a 3d experience, which is exactly what it should be.

Looking back at your first steps in music with Hotlegs and the success of Neanderthal Man, you reflect in the book that you feel as though you sold yourself in many ways to the commercial aspect of the industry. How much did this experience contribute to the formation of 10cc and its success?

Kevin: I think everything we did up to that point contributed to it whether we knew it or not. What we were doing essentially was learning by doing. Although some of the stuff we did we didn’t think was great, every time we did anything it coalesced in our brains without us knowing it was happening.

I get the impression in the book that Strawberry Studios in Stockport was the perfect environment to find yourself and to have that period of trial and error?

Kevin: We were incredibly lucky. We were in a unique situation in that we were away from the main hub of the music business being out of London and in the sticks. Therefore we had the run of the place when it wasn’t being used as a commercial studio and we were allowed to play, which is exactly what we did. We played as opposed to working. The whole experience was a sort of voyage of discovery.

10cc from left to right: Eric Stewart, Lol Creme, Kevin Godley, Graham Gouldman.

Sticking with that experimental time, I read an article recently in which Eric Stewart said that you guys worked in pairs a lot. That himself and Graham would go and write something and that you and Lol (Creme) would go and do the same. Was that the way it worked at the time?

Kevin: Thats the way it started because Eric and Graham weren’t a natural team whereas Lol and myself were. We’d been working together on and off since we were kids, so it was a natural birth. Later on in the process we swapped partners and tried things that way, but initially, because everybody had a certain aesthetic and a certain sensibility, somehow the chemistry when the four of us were working in different ways brought the best out of us. We were all aiming at the same point on the horizon, so we all went the extra mile to make sure we got something.

It seemed that even when you were in conflict it would benefit you. Theres a rumour that when Eric came to you with the original idea for I’m Not In Love, that you initially didn’t like it. Is that true?

Kevin: It wasn’t the song so much as we didn’t quite know what to do with it. The first recording of it was a bit cheesy. It was like a loud Bossa Nova thing, and it didn’t work for the song, but we knew there was something there. So, we put the first recording to one side and carried on making that particular album, and then came back to it with a desperate idea. I said if we don’t know what to do with it lets try something really crazy. Lets forget normal instrumentation and just use voices. Lets create a wash of vocals for this to sit on. We found some magic in that and it got to a certain point where the record kind of recorded itself. It was a serious of magical sessions for some reason. We had discovered something.

Moving on to the music videos, its seems to have been a constant desire in your career to combine audio and visual, and you had immediate success with the video for An Englishman In New York and videos you did for Toyah Wilcox and Visage. This was at a time when the visuals were just becoming part of the process. Did you feel you had complete free reign and creative license as a result as there was no real expertise to compare with?

Kevin: Initially, to a large degree, yes. Nobody really knew what a music video was supposed to be. The suits didn’t really know yet what it was about this medium that would help their audio become a success, so for the first few years there was a sense of lets leave it to the creatives and see what people like watching. It was a case of the lunatics running the asylum. With this, we were there at the beginning so we could help dictate what this new medium was all about.

Two very different projects came your way in 1983, which you referred to in the book as signposts in your life. These were of course Herbie Hancocks Rockit, and The Police Every Breath You Take. The finished product for both couldn’t be more starkly contrasting. What was it like directing these two very unique videos at the same time?

Kevin: It was brilliant. We discovered a natural empathy for the medium. We were audio magpies and now we became video magpies, in that we didn’t have anything that represented who we were. We just applied ourselves and applied our thought processes to what we heard, and thought these pictures will go with this track. It was very simple for us in that respect. For instance with Rockit, had I not seen that clip on the local news programme it may never have been made.

You eluded in the book to some controversy surrounding that Herbie Hancock video, as MTV refused to feature a black artist on their channel. How you did you overcome this?

Kevin: At that time MTV only existed in the states, and we had no idea that such a situation existed. It was a shock to the system but it was also a challenge. The idea to display Herbie through a television screen in the video, we didn’t know whether they’d go for it. Like I said in the book we felt that people would be so side-swiped by the robots, they wouldn’t even notice that Herbie was black!

Looking back at some of the earlier videos you’ve directed, and then some of the more recent ones you’ve done for the likes of Snow Patrol, Katie Melua and Boyzone. What is the difference in the process and has there been any change in your own approach towards directing videos?

Kevin: Not really. I suppose I’m always looking for something thats going to please me because I’m a fan of the medium. Then, I ask myself well has this been done before, and if the answer is yes then I move on. The thing for me is always to create a film that is watchable, but is watchable because nobody has seen this idea before. Thats what attracts me to the process. The continuous challenge of creating something original.

Your boyhood dream came true when you got the opportunity to direct a video for The Beatles song Real Love. What was it like to work with the greatest band of all time and having access to so much rare and unseen footage such as Yoko Ono’s home video of John Lennon?

Kevin: Well like you said it was a dream come true. Probably the most embarrassing thing was the mix that we had wasn’t a great mix, and the label were a little sensitive about the track getting out there before they’d finished mixing it properly. So we got a kind of compromised mix and I couldn’t hear the vocals too well. So just so I could clarify what was going on I stepped into a recording studio and added my own vocal on the top so I could understand what the song was saying. And that is actually out there somewhere to my eternal embarrassment.

You were reunited with Sting for the BBC Two special One World One Voice in 1990, which you directed, and you mention in the book how the idea was something that had been itching away in your mind for quite a while. How did idea meet opportunity?

Kevin: Well I had the idea in my mind sometime before Godley and Creme separated. I have no idea where it came from but it was one of those ideas that stuck around and when I was asked to go and meet these guys it was like hang on a minute what they are asking for, I have. It might have been slightly radical at the time but thankfully they went for it.

The process was incredible. The way it was done, you’ve described as ‘chain tape’. How exactly did you manage to create a collaboration of music between artists who were in completely different parts of the world at the time?

Kevin: With difficulty! There was no e-mail then. There was no dropbox. When we filmed and recorded something we had to Fed-Ex tapes to people across the world, and they would rehearse their parts and then we would show up in their city and record them and we would do the same with everybody. It was all very analog and all very primitive. It was probably the craziest thing I’ve ever done.

This idea for One World One Voice was the seed that formed the WholeWorldBand app that you’ve brought out recently. This seemed like the pinnacle for you in terms of your creative existence, creating a music platform that combines both audio and video in a way that resembles a global recording studio. Has it lived up to your imagination now that it has been out for some time and people have experimented with it?

Kevin: It’s exciting for me to see what other people do and to see how other people look at the possibilities of what this thing is. I kind of check into it every evening before I crash out and I see some guy playing his guitar on a folk song or somebody playing timbale on a Taiwanese flute! Thats what it was all about, to find out what people can come up with when they have the freedom to play with anybody and anything.

I’d just like to mention how sad I was to hear the news of Dennis Sheehan’s death, U2’s tour manager, who is someone I know you’ve worked with quite a bit over the years.

Kevin: Oh I couldn’t fucking believe it! I just couldn’t believe it! When I was working with U2, which I’ve done many times and been on tour with them, we always used to end up in the bar with Dennis and Larry and chat until four in the morning and now he’s gone. I mean christ almighty! Life is so unfair.

Sticking with U2, the chapter on the making of the Sweetest Thing video was one of the most entertaining in the book for me. How difficult a task was it to try and convince Bono to not be serious for once and to be funny instead?

Kevin: Well it wasn’t that hard because it was a natural moment, as soon as he put the hat on he was. Then as soon as he started to think about it he was like ‘wait a minute, do we really want to be funny?’, but there was no escaping it at that stage that was the way to go.

Looking at that relationship with Bono and U2 and how it developed over the years from Numb to Sweetest Thing, is there a reason why they are a band you’ve worked most frequently with? Is there a chemistry that is immediately struck or is it a relationship that gradually builds and grows?

Kevin: I don’t know I’ve never really though about it. I suppose its quite obvious really, if you do a good job for someone they’ll probably come back. We got on well and enjoyed the process but particularly from my perspective, they give you free reign to come up with ideas but in the end, because they know and understand the medium they will take part with you in every aspect of what it is. It’s important to them that the finished product is as great as it can possibly be. They like to remain involved during the process, which I find enjoyable because having other minds helping you along is really useful sometimes and they really know their stuff.

I’m interested in your own take on the music industry today. You say in the book that pop music ‘has a habit of circling back on itself and starting from scratch before it gets too up its own arse.’ Why do you think this is the case?

Kevin: I think it comes down to access. I think technology is so dominant in our lives that we can listen, watch and experience things quicker and more instantaneous than we could before and therefore we digest quicker but we also spit out quicker too. So there is more of everything, and thats good in some ways but there is also a downside in that the concept of a rare object no longer exists, and I think to a degree we are spoilt in the way in which we are entertained. With any progress that takes place, I believe there is a downside to accompany the upside and thats just a matter of opinion.

Reverting back to music again, I had a listen to the GG06 project and the six tracks you recorded with Graham. Was this you wanting to venture back into the past and relive 10cc with Graham or were you looking to explore something new?

Kevin: Well I just wanted to make music again but I didn’t want to go through the whole rigmarole of creating a relationship with somebody new. I just wanted to write something, so I thought why don’t I find someone I know and all that shit can disappear and we can just crack on. It was interesting because Graham and myself wrote very little in 10cc, so now was the opportunity to try and write something properly as opposed to just being thrown together as a small experiment in a bigger picture. I wanted to write stuff that was more real. I felt we wrote ourselves into a corner in 10cc in the end so I wanted to get away from that and write about stuff I understood.

Your innovation and creativity has never dwindled throughout your career. Whats next for you? Do you still have the appetite to experiment with your music and create?

Kevin: To a degree, yeah. I’m working on a project now that involves music but its not on album. It’s what I call an ear-movie. It is essentially a play or movie in sound only and it’s called Hog Fever and it stars Terence Stamp as a shrink. I think its going to be released as a podcast on June 1st and then in August we’re intending to release all six parts on numerous platforms, possibly even vinyl.

Spacecake is now available to download now from iBooks.