While it was originally released in 1972, it very quickly disappeared and only received a CD release earlier this year. A little context is necessary: The Watersons were the first family of the ‘60s folk revival. They had made a name for themselves in creating very pure, very faithful reproductions of the British folk traditions. Their style was stark and unadorned by anything that could be described as modern, singing as they did songs that dated back decades, if not centuries, and singing without instrumentation, they sound like the recordings themselves may date back that far too. So when Lal & Mike released this album of new songs with ‘new’ instrumentation (I placed new in inverted commas there because there is nothing that might strike us as modern), it was viewed as something like a betrayal.

The second thing I should note before I really dig in is to say something about Lal & Mike – their voices are as stark as the songs, fully embodying the North East; cold, stern, bitter, devoid of obvious signs of warmth. The production, even when adorned by sympathetic arrangement, still pushes the vocals up front. There is something very Nico-like about this, where the voices are strong and imposing and forcing themselves upon all else.

But then, the songs. While they fit into two broad types; the jaunty and the not, the lyrics maintains the subject matter of the traditional materials; nature, death, despair, isolation. Danny Rose is, to the ears, a light rock’n’roll style number and is possibly the most upbeat here, is about a violent thief who stole a car, crashed it and died in the subsequent explosion. The Magical Man is again jaunty, apparently celebrating a mysterious magician. Closer looking at the lyrics suggests something sinister.

But then, the stars of the show are the ballads sung by Lal. The combination of her deep sonorous voice, foreboding and the solo guitar and light-touch arrangement of strings is honestly spine-chilling. To Make You Stay sings a song of abandonment. Never the Same tells a horrifying story Rosemary’s death on the hillside.

But Johnny can’t play no more, Rosemary’s lying in a shower of rain.

If we live another day, We’ll never be the same again.

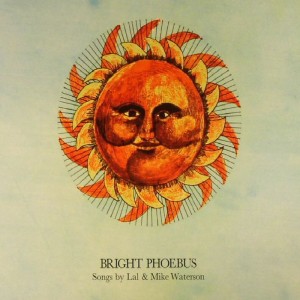

The album closes on the title track, which refers to the sun. While it is, ostensibly, a happy song – it is lovely when the sun comes out for the first time – there’s something a little Wicker Man about it. Why is it the very first time? And here we find another striking parallel – a picture of an England gone by brought into contact with (1970s) modernity producing something both beautiful and a little unsettling.

[I have re-purposed this from the ’10 Albums from 1972′ article that is forthcoming.]