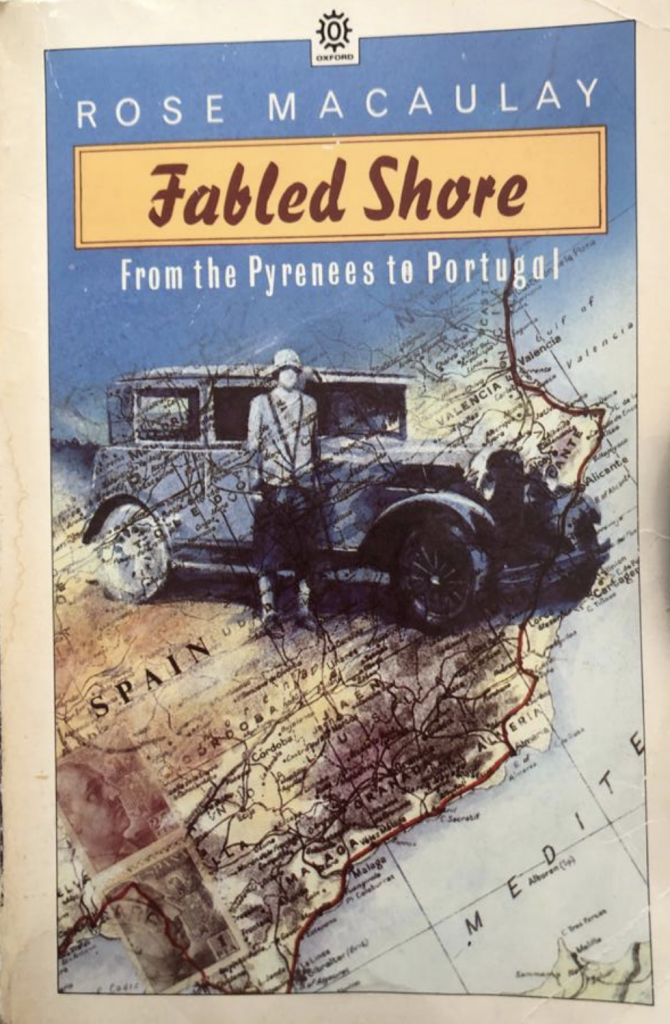

In 1949 an English woman named Rose, with an extraordinary knowledge of history and architecture, hired a car and traced a journey around the east and south coasts of Spain and Portugal.

Her primary interest, it would seem, was not so much to understand and be exposed to the Spain of her time. Instead it was to hear the echoes of the many nations and peoples, who through the centuries, had made themselves a home, life and civilisation on that coastline. She did this through immersing herself in a study of the:

- Architecture that such civilisations left in each town and village she passed by, musing at grassy foundations as much as old ports and churches still intact.

- The geography of the Spanish coast.

- The crops, plants and fruits that were grown, processed and traded.

- People and their customs, although this book was hardly a detailed ethnography.

Rose MacAulay was not just interested in historical fact. As the title of the books suggests she was also very much taken with those parts of history, which are sufficiently poorly documented or backed up, that one no longer knows whether one is dealing with fact, popular myth, the lies of an author or a blend of all three. In this way MacAulay loved to provide conjecture on the possible location of fabled towns and monuments. Furthermore, where the facts were clearly known she loved to re-imagine historical scenes and events

All in all, Rose MacAulay’s book was a beautifully selfish account of her trip to Spain. What I mean by this is that she wrote as if for herself, or at least for someone with her incredible knowledge of history, recent to ancient, and mythology, Greek, Roman and the like. There is no preface to the book outlining the key points of her knowledge. Instead she simply dips into it cursorily in helping the reader understand why she went to see what she saw and how she made sense of it when she did see it.

In this way the book is unlikely to provide the reader with a coherent account of the history of the Iberian peninsula. Perhaps more excitingly it instead provided glimpses into that history as it pertains to the places and observations that MacAulay makes sense of, and gives one a hunger to better understand that history.

All the way down this stupendous coast I trod on the heels of Greek mariners, merchants and colonists, as of trafficking Phoenicians, conquering Carthinigians, dominating ubiquitous Romans, destroying Goths, magnificent Moors, feudal counts, princes and abbots. History in Spain likes like a palimpset, layer upon layer, on the cities, on the shores, on the old quays and ports, on the farm-houses standing among their figs, vines and olive gardens up the terraced mountains. Ghosts from a hundred pasts rise from the same grave, fighting one another still, dig a little deeper, dig below the Moor to the Goth, below the Goth to the Roman, Carthiginian, Greek, Phoenician, and in the end you get down to the Spanish, who were there before history began, and will be there after history, defeated and routed at last by this strange land, impenetrable mists.

Furthermore, it puts Spain into three dimensions, it creates a layer cake out of the country, and gives you a sense of the different peoples, civilisations and cultures that have come along and added their footprint to the east and south coast, if not the whole country. Finally, it means that the reader can relax and through Rose feel equally as indulgent, as she meanders.

I have read the book as an Englishman who has spent a good deal of time living in, getting to know the country and its inhabitants. Reading it in 2020, the year of the coronavirus, lockdown and quarantines, it has been a marvellous substitute for my usual annual summer pilgrimage. On this page I seek to relate my own experiences to those of Rose, and to also do further research on some of Rose’s discoveries and experiences, to find out more but also to see how things have changed in the seventy years since.

This review will very much be a work in progress. If you would be interested in receiving notification each time a significant update is made please email me at vanguardonline@hotmail.com

I would be delighted to hear from fellow Iberophiles and anyone who has read the book so please feel free to comment below or using the email address.

Society

I read Rose MacAulay’s book principally because I was interested in how she encountered Spanish society in the years following the military victory of the fascist dictator Francisco Franco over the democratically elected Republican government. When MacAulay visited she was visiting a Spain which had become a fascist dictatorship, and a Spain, following the end of the Second World War, which had become politically isolated in the world. On this account I was disappointed as MacAulay offered little interest or insight.

Still there were nevertheless several themes developed in the book, which were of some interest.

The kindness of the Spanish

Rose MacAulay was taken aback with the kindness of Spanish people, which she felt exceeded the kindness of any other peoples she had encountered.

Public social life

The art of socialising in public settings

I almost wanted to cry the time I went to Bilbao in 1999. I went with two people from England, we were invited to the house of a Basque friend of one of my travelling companions. After having visited the Guggenheim we took a tram to the house, which was in the suburbs on the edge of the city I imagine. There was amongst the suburb a triangle of public land, with trees and benches in. At seven o’clock in the evening it was teeming with young children playing together, and their parents and various other adults chatting. Although it was probably just another evening in Bilbao for the locals, it was for me a baptism into a new reality, a social reality where people were friendly to each other, knew each other and specialised in the art of enjoying each other’s company. In England, something like that didn’t and still really does not exist. Don’t get me wrong – we do have playgrounds – which is the nearest we come to it. But this wasn’t a playground, it was a public space, it was a daily evening ritual, in which local people, came out and did what they did every evening, enjoy each other’s company, regardless of whether they have a three year old who needs to be pushed on a swing. The cherry on the cake for me was seeing so many older relatives who had been wheeled out in their chairs, into the triangle, so they could join in, and be a part of it, and feed of this very positive social energy. My mind wanders back to a scene in Jordanthorpe, Sheffield, where I once walked, and the shopping centre there, which looked desolate, and the only people who walked around were young adolescents who looked bored, unhappy and threatening. How did we get it so wrong?

Four years later I found myself back in the Basque country, this time in the much smaller town of Durango. Real Madrid were playing Athletic Bilbao in the last game of the season – if Real won they would take the title – if not it would go the Basque team from San Sebastian, Real Sociedad. I remember a bar in Durango packed with men and women sat on stools watching the game, drinking beers. Real Madrid won, which was a real disappointment as it could have been good to witness the Basques celebrate a rare league victory. However what I remembered equally was not the football so much, but the fact that whilst the adults were watching the game in the bar, there were some dozen children of different ages from two upwards, running in and out of the adults as they were sat, and in and out of the bar, from eight when the match started, to twelve midnight, when the punters started to go home. In Spain the children are a fixture of social life, all the way into the night, as much as football and as much as a beer. Again, it warmed my heart, and I thought about the complete absence of children in almost all night life in the United Kingdom. Again, I realised that Spanish culture, had, for whatever reason, an inbuilt custom for celebrating being together, they really understood the art of enjoying each others’ company in social public settings.

I was thus delighted to read of Rose MacAulay experiencing the same kind of wonderment when visiting Denia, in Valencia. MacAuley was even luckier in some respects, because she witnessed what appeared to be a weekly dance and and live music.

It was a lovely sight and sound, those dancing Valencians, men, women and children, footing it in the lit, trellised court above the glimmering sands and darkening sea…. There were a great many small children with their parents; supper was not till after ten, so they made a night of it, as, indeed, the children of Spain always do.

Alcohol and drunkardness

It really hit me the night I found myself walking around Pamplona on one of the evenings of San Fermin. There were crowds of people here and there drinking outside bars, charangas playing gay tunes and hundreds of pairs and groups wandering around with beers in their hand. However, I noted, that at no point did I feel cowed or scared. Unlike in the United Kingdom I found that whilst the Spanish liked to drink, wine and beer, and many other things, they seldom got drunk, lairy or aggressive. It seemed that everyone was in pretty good spirits and that if they weren’t they weren’t going to try and ruin it for everyone else.

Rose MacAuley found the same thing. She said:

Another thing about the Spanish – they never seem to get drunk. The only intoxicated people I saw in Spain were one or two Britons.

Its not that Spaniards don’t drink, and in fact I’m sure they drink enough or as much as many English people, but its just why they do it, and how they respond to it, which is as much to do with how they feel about themselves, where they live and what they do, as much as anything else, that is so different.

Women’s subjection to men

In Church

Throughout the book Rose MacAulay explored women’s subjection to men. In many ways Spain in the late 1940s resembled what we might expect in a strict male controlled religious society in the middle east or north Africa.

MacAulay noted that women were subject by church clergymen to strict dress codes. In Cadaques, the home town of Salvador Dali, she explained:

It was in the porch of this church that I first read the placards, which all over Spain, warn senoras and senoritas what they must wear in church. ‘Senora! Senorita! You present yourself without stockings? In a short dress? With short sleeves? You go into church? Stop! Stop! If you go thus into church, you will be turned out. If you go thus indecorously to confession, you will not be given absolution. If you have the audacity to approach the Blessed Sacrament, you will be refused in the presence of all.

That such signs were published outside of churches suggests that not all women were willing to oblige such expectations.

In Work

MacAulay noted that most petrol pumps in northern Spain, as in France, were worked by women. In contrast she noted that further south women did not do the same job. She pointed out that women ‘were not to meddle with anything to do with motoring, they stick to donkeys’.

The difference in women’s relation to paid work between the north and the south of Spain resonated, in some small part, with my own experiences. In the Basque Country it was clear that the women (as well as the men) appear to, in general terms, have a more rugged physiology, outlook and behaviour. It is perhaps not a surprise that in the forties they were generally more expected and therefore enabled to carry out work and activities reserved for men in the south. An important factor in possibly explaining this difference was the industrialisation of northern Spain, in the Basque Country and Catalonia, which perhaps provided more demand and opportunities for women to take on paid work.

This discussion reminds me of the fact that when I was teaching in the Basque Country I came across a small but noticeable number of girls, who appeared to me to be boys. In one class that I taught there were a couple of girls, who I had assumed to be boys for a week or so. I received the shock of my life when ten days into teaching, and after having asked the class to split up along gender lines, they insisted on being with the girls. Both girls had been surly and fairly unruly throughout my time with them, which had added to my thinking they were boys, and when they first put themselves in the girls’ group I had thought that it was yet another occasion of them attempting to disrupt the class. I insisted that they move to the boys group, but it was only after the whole class tried to convince me they were girls, and I started to detect a hint of humiliation spreading across their faces, which were usually contemptuous, that I too, felt a mixture of shock and guilt. One prominent Basque teacher informed me that the Basque Country seemed to have a higher than usual proportion of girls, who appeared to want to be, looked like and behaved like males. I think I’m right in remembering that some children were said to be seeing some kind of professionals to help them talk about and reflect on their identity. I don’t remember or know if the purpose of the professional intervention was to challenge or support such children.

In Relation to Driving

MacAulay’s journey around Spain, by herself, in a motor car was notable for the fact that in the 1940s no women were able to or encouraged to drive. MacAulay pointed out that no woman of wealth were not expected to drive.

So few foreign senoras are seen driving that they are still regarded as prodigies and potents, much like a man sucking a baby.

Men were astonished to see MacAulay driving a car by herself and some responded with intimidation and humiliation:

All over Spain, except in the more sophisticated cities, my driving by way greeted with the same cry – a long, shrill cat-call, reminiscent of a pig having its throat cut, usually wordless, but sometimes accompanied by Ole, Ole! Una senora que conduce!… The demonstrations sound mainly astonished and derisive; sometimes rather inimical; always excited and inquisitive.

MacAulay noted that it was not as if women didn’t drive at all. Peasant women she said were often seen driving donkey carts. However in the 1940s they could not afford a car of motorised vehicle.

Being Alone in Public

Quite aside from whether she was driving or not MacAulay also found Spanish people tended to point and stare when they saw her by herself in their town. Part of this she put down to being a foreigner. The Spanish she argued, were for historic reasons, particularly sensitive to the presence of foreigners.

In the matter of starting, history is probably too strong for them; they have been so often invaded, assaulted, plundered, occupied by foreigners down the ages – Carthaginians, Romans, Goths, Moors, French – that excitement about what foreigners are up to may be in their blood.

MacAulay noted that the Spanish tended to call any foreigner Frances.

…walking about Barcelona bare-headed after sunset, mixing with the cheerful crow that thronged the ramblas, with only a finger pointed now and then, and an occasional cry of ‘Frances’, was very pleasant.

This jogged my memory of a time I stayed with a family in Gijon twenty years ago. One of the family, a man with Down’s Syndrome always used to refer to me as frances. He also remarked on how much I looked like Jose Maria Aznar, principally because I had facial hair.

Although she suspected that part of the interest was in her being ‘foreign’ she also felt that ‘particularly their interest is in woman, and more particularly in a woman alone’.

The fact of her sex, and the fact of her aloneness, seem to the Spanish at once entertaining, exciting and remarkable, as if a chimpanzee strayed unleashed about the streets. For Spanish ladies do not travel about alone.

Children it seemed were particularly keen to chase and follow around the towns she visited; and in this way were a permanent fixture that needed to be navigated as she digested the ancient history of the relics and buildings she visited.

The best thing about the cathedral is the cloister, with its lovely lancet arches and its richly carved capitals. I inspected these, stalked silently and at last a distance by a mob of boys who had spied a stranger, and, in the usual Spanish way, deserted all other pursuits and enjoyments in order to track her. … Followed, then, by these hunters lurking behind pillars and fleeing if I looked round, I examined the charming and various capitals, carved with donkeys drawing castles, knights chain-mailed to their teeth….

Wherever MacAulay went, and wherever it happened (and it happened alot) she always wrote about in good temper and being always forgiving, tolerant if sometimes a little perplexed. One of the most extreme experiences, she dealt with a great deal of humour. It took place in the border down of Ayamonte close to Portugal. Not only did a mob immediately attach themselves to her, they followed her on to a ferry, which took her to a nearby island, followed her around the island, and then beat on the door of the place that she stayed whilst she ate dinner, in the presence of a policeman, who would have seemed to have been sent for to protect her. She recalled:

I asked the policeman if they never saw foreigners in this frontier town, and why they were so excited; for I half supposed myself come to a colony for those not right in the head.

Not all though and she noted that sometimes a disapproving elder might apologise for the behaviour of her compatriots and ‘will sometimes attempt, vainly, to call them off’. She mentioned a customs official hitting a group of children who had climbed into her car, over the head with a bundle of passports.

MacAuley in providing her glowing account of children playing in Denia, did also note that whilst she had seen girls and boys playing in Denia, in most other cases the children had tended to be male, hinting once again at how Spanish society, in the 1940s involved men working to control and ensure their ownership of women.

…. In any town or village you may see [children] playing in the streets at midnight – or rather, you may see the little boys, for little Spanish girls in cities seem to lead rather immured lives, in the old Arab tradition.

Signs of the Civil War

The Spanish civil war was not just a Spanish war, it was one which involved the Germans, Italians and Soviets. In some respects it was a warm up for World War II.

Rose MacAuley’s book was quite clearly not an attempt to understand the type of Spain that had emerged out of the ashes of the war. She did, however, make a few references to the legacy of the war.

In Alicante, for example, she noted that the punishment given to the city for ‘backing the wrong side’ was to have its streets named after several of the leaders of the military rebellion.

She noted that the house of Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, the Founder of the Falange, had been consecrated into a chapel. Reading this in the section on Alicante made it sound like the house had been in Alicante. However a brief search on the internet suggests that MacAuley had been referring to a house in Madrid.

Primo de Rivera, who had been a prisoner at the time the civil war began, was executed by the Republican government at the start of the civil war. His political activities had been funded by Mussolini, he had advocated violence against the democratically elected government and was presumably in favour of the military rebellion. A large part of the Catholic church was in favour of Franco’s military rebellion and the slaughter of anyone who resisted. By consecrating Primo de Rivera’s house the Catholic church elevated Jose Antonio to the level of a spiritually pure man in keeping with God’s will. It was ultimately the stamp of approval of the Catholic church and by Franco.

The French

I had never appreciated the level of dislike in Spain for France before I read Rose MacAuley’s book. In the United Kingdom it is almost as if there is no European history before the first and second world wars. We are not taught that in the early 1800s it wasn’t Hitler’s Germany that was rampaging around Europe, but instead Napoleon’s France. In 1808 Napoleon invaded Spain, which led to a war, one of several that Napoleon had started, that was resolved in Spain’s favour in 1815. However during the time that the French were in Spain they caused havoc. MacAuley has them looting, vandalising and blowing up parts of the Alhambra in Andalucia. Since this point, MacAuley implies, the Spanish have never been particularly fond of the French. She adds that French tourists could, from time to time, in the nineteenth century, find themselves subject to stoning and humiliation, and especially in Granada.

Anecdote and peculiarities

I had read MacAulay’s book also hoping to pick up some anecdotes and features of Spanish life that I could relate to. Again the book was not full of such things, but there were one or two pieces that particularly resonated.

The Spanish determination to speak English

My experience of educated Spanish people with regards to English, is that they are determined to speak it even if you can speak better Spanish, they hate being corrected even if their accent and grammar is full of mistakes and they have an unchallengeable belief that they have mastered it. It thus caused me much mirth to hear of MacAulay’s account of an interaction in English with two people in the Catalan town of Figueres.

I and my car were guided to an hotel by a kind youth who was studying English and collected stamps; for both these hobbies he found me profitable, though, for all I understood of what he said, he might as well have talked Catalan. He collected and introduced me to his instructress in English, a smiling little bespectacled lady who conversed with me in the street, but seemed to understand the remarks she made to me better than those I made to her; with me it was the other way around. She said, ‘You make long stay in Figueras?’ I said, one night only. She said, ‘You will be a week staying, yes.’ I said one night. She said, ‘Yes one week. You like Figueras.’ I said it was beautiful. She said, apologetically, that she could not quite understand my English, which was not, was it, of London. She said some more, in the English of Figueras, and we parted with mutual compliments and friendship.

Church bells through the night

One my first introductions to Spain was to lodge with a family in the Basque country in the early part of this century, as part of a programme for teaching English to young children during the summer time. I stayed in a village buried in the mountains, in a quaint terraced house, made and smelling of wood. I slept on the first floor under the rafters of the house. It would the most beautiful place to sleep if it had not been for the church bells, which not only rang the number of hours which had passed since midnight and midday, but also marked every quarter and half hour. During the day such noises were, once again, quaint, but at three in the morning, they were akin to being bludgeoned, and I would be stunned awake. A poor sleeper anyway, the result would be that by the time I got into the school to teach, I felt nothing more than a zombie. The impact of the church bells was compounded by the fact that there were not one but two churches in such a small village and the timekeepers were clearly not in agreement over the exact moment at which a quarter, half or full hour had passed. Until reading MacAulay this had been a purely personal suffering:

I like the people of Figueras. But not the church clock, which made the night unquiet by resonantly striking every quarter. Wakeful and fretful, I began to understand the Spanish passion for churchburning.

Church burning

MacAulay noted throughout her book that the Spanish were given to fits of church burning. She called it Spain’s ‘second national sport’. 1835 was noted as a vintage year, and she referenced several churches burned down during the war in Spain in the 1930s.

MacAulay explained that in 1835 the context to the resentment directed at the church related to the feudal powers of the monastery and its monks, which included possessions of the estates, but also included kidnapping, torture, extortion and rights to the bridal night.

MacAulay’s use of the word ‘piccanniny’

In Loulé Rose MacAulay talked in rather poetic terms about seeing people, who appeared to be Black.

You pass the arcaded slave market; the descendants of those terrified, weeping Africans and Canarians walk the streets to-day in blithe liberty; their piccaninnies, with little white shirts and great shining black eyes, goggle at strangers with the same merry astonishment with which the Lagos children gaped at the poor blackamoors five hundred years ago.

I was struck by MacAulay’s use of the word piccaninny, not least because Boris Johnson had been reported to have used it on public duties. When Johnson was reported using the word this bought to my attention both the word itself and the fact that it was understood to be a racist term. It made me wonder about the social context in which MacAulay felt it right and acceptable to use the term. Consulting the web I found that the term has a Spanish origin, being a derivation of pequenin, which in Spanish means ‘small one’, used by Black people in the West Indies to describe their children. Subsequently, apparently, the word was taken on by White people in Canada and the United States of America, and used as a form of racial slur.

Ethnic and cultural legacies

Throughout her book Rose MacAulay claimed to see the ethnic and cultural traces of the different peoples who had commanded some part of the Iberian peninsular over the last three thousand years.

She could see it in peoples’ faces. For example, in Valencia she said the people had a ‘classic beauty so often the outcome of the happy fusion of Moor, Iberian and Roman’.

She could also see it in peoples’ behaviour, dress, language, music and architecture. She saw Africa in the ‘minaret-like, lustre-tiled deep blue church domes’ in the Valencia region.

MacAulay’s palimpsest view of Spain and its people provides a more nuanced and international understanding; one that implicitly and softly mocks the myths of Spanish nationalism and identity; and the particular strain that its determination to set the Spanish identity in contrast to the Moors and Islam. Indeed MacAulay almost makes this point herself, when she comments on seeing what she considered to be the ‘handsome brown Moors’ of Villajoyosa having its annual fiesta for the defeat of the Moors seven centuries ago.

It was interesting to see the handsome brown Moors of Villajoyosa making so merry over the defeat of their relations long ago.

The fiesta, which is called Moros y Cristianos, still takes place in late July (here for the organiser’s web page).

In Burriana MacAulay fancies that the town and its inhabitants are Moors, Moors living under the yoke of the Spanish state.

Oranges, even in high summer, are piled on every market stall in the towns, and in the panniers of the small donkeys that smaller boys ride about streets and roads; one can eat as many as one has a mind for, thanking the Moors for their intelligent irrigation. Moorish engineering, Moorish castles, Moorish-looking minarets and domes, Moorish faces and songs, memories of Moorish battles against the armies of Jaime the Conqueror, who fought them all down this coast and hinterland and finally beat them and took their kingdom, but still they stayed on the land, and their Moorish-Iberian descendants now darkly and beautifully ride their donkeys about the roads, and walk gracefully from the water troughs with their tall Moorish pitchers on their heads.

The latter of course was a result of the determination of the conquistadors acting under the fascist Spanish Kings to rid Spain of any Islamic or Jewish influence. There has since this time long been a dominant Spanish political determination to continue this. The point that MacAulay makes is that Spanish architecture, behaviour and ethnicity has long been and remains, even by those who don’t identify with it as Moorish, north African and Islamic.

She referred to ‘the little African town of Callosa de Segura‘. She described the surrounding land like so:

Each village had its little domed and miniareted church. The landscape, the buildings, the climate, seemed of Africa: so did the dark turbaned people riding their asses long the dusty road.

History and Geography

The Pillars of Hercules

Frequent reference is made in MacAulay’s book to The Pillars of Hercules. These it turns out refer to the promontories that flank the straits of Gibraltar. One of those pillars is the Rock of Gibraltar, the second is said by the Encyclopaedia Britannica to be one of two peaks in northern Morocco. According to MacAulay in Greek mythology a chap named Herakles clove a bridge of land between Africa and Europe in two, creating the straits and the pillars. Curiously enough it was about the time of the publication of MacAulay’s book that scientists started to find evidence to suggest that the straits of Gibraltar, had at one point, some 5 million plus years ago to be exact, joined to effectively form a barrier between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. This led to the drying up of the Mediterranean Sea, which turned into desert. Following this, with rising sea levels, scientists hypothesise that 5.3 million years ago, the Atlantic Ocean reflooded the Mediterranean, in what MacAulay might have like to imagine was a Heraklean event.

‘The Rock and Defences‘ by chantrybee is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Greeks, Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Romans, Goths and Moors

Rose MacAulay, from the beginning, consistently made reference to the waves of people who attempted to colonise the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula. Greeks, Romans and Moors I had heard of. Phoenicians and Carthaginians I was less sure of.

The Phoenicians I find out spoke a semitic language, came from Lebanon and set up trading posts all around the Mediterranean between 1100 and 200 BC.

Carthaginians are also referred to as Phoenicians, which makes me wonder why MacAulay drew a distinction between the two groups. In any case the Carthaginians’ principal legacy is the city of Cartagena, which takes its name from them, to be found on the southeastern corner of coastal Spain.

The Romans, it would seem, held sway in Spain from around 200BC to 500AD.

Around about 500AD the Roman Empire was defeated by various Germanic tribes, who invaded and ruled Spain for 300 years. They included the Vandals, the Visigoths and the Suebis.

From 700 to 1200 AD the Iberian peninsula was ruled in large part by a succession of Moorish Muslim peoples.

Around about 1200 AD various Christianised tribes in the Iberian peninsula, often backed by Christian tribes from elsewhere fought and eventually defeated the Moorish peoples.

Port Lligat, home of Salvador Dali

MacAulay visited Port Lligat in Catalonia, a port which she described as having three or four fishermen’s cottages, of which the white one of Salvador Dali was said to stand out. She described Lligat as having a ‘fascination not incongruous with Dali, and not quite of this earth’. The house, which Dali points to in this photo, contained a studio where Dali did his work, and is currently a museum. A documentary about Dali’s relationship with the house appears was made in 2017.

Figueres, in Catalonia, the last capital of 1930s Republican Spain

MacAulay brings the reader’s attention to the fact that Figueres, in Catalonia, was, for a short time, the last capital of 1930s Republican Spain. It would appear that the democratically elected Spanish parliament had their last meeting in an 18th Century San Fernando fortress in Figueres, having fled from Barcelona. Franco’s forces took the city seven days later. MacAulay reported that the Republicans blew part of the fortress up before they left it.

Catalonia, land of castles

I learned from MacAulay that the name Catalonia means ‘land of the castles’. MacAulay explained that at around about the turn of the first millennia Catalonia was under the control of the Franks, a barbarian tribe from Germany. Further research adds that the Franks controlled France and Catalonia from the 800s to 1000. It is from the Franks that France took its name, and it is from the Frankish custom for building castles, that Catalonia, which began to become an independent state in around about 1000 AD took its name.

It was the Frankish counts who set the tradition of the small Catalan walled town as we see it today – high, ochre-brown citadels, many of the houses arcaded and terraced, tiled roof climbing above tiled roof to the solid, fortress-like church that crowns the pile, with its heavy nave and apse and square tower – embattled churches, with belfries like watch towers to observe and clang the warning news of approaching foes… Many have castles…

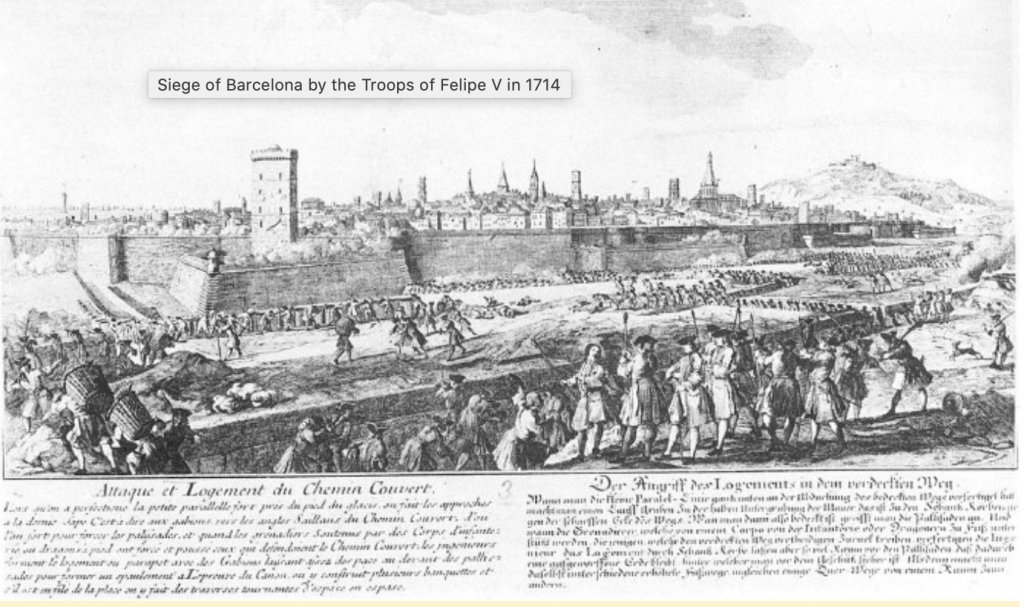

Barcelona’s town walls, dismantled in the 1860s

MacAulay was greatly taken with the colour and excitement of Barcelona. She noted that the city had ancient town walls, which were demolished in the 1860s. Further research suggests that they were dismantled to aid the growth of the city and improve the health of Barcelona’s denizens. Here’s an image of what the walls looked like a hundreds years prior.

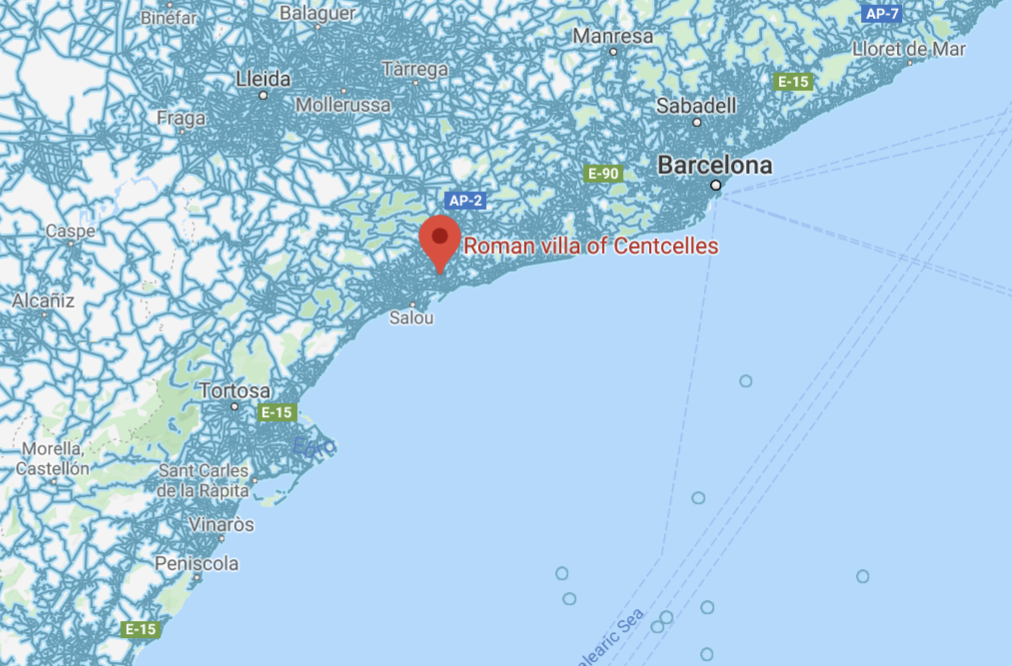

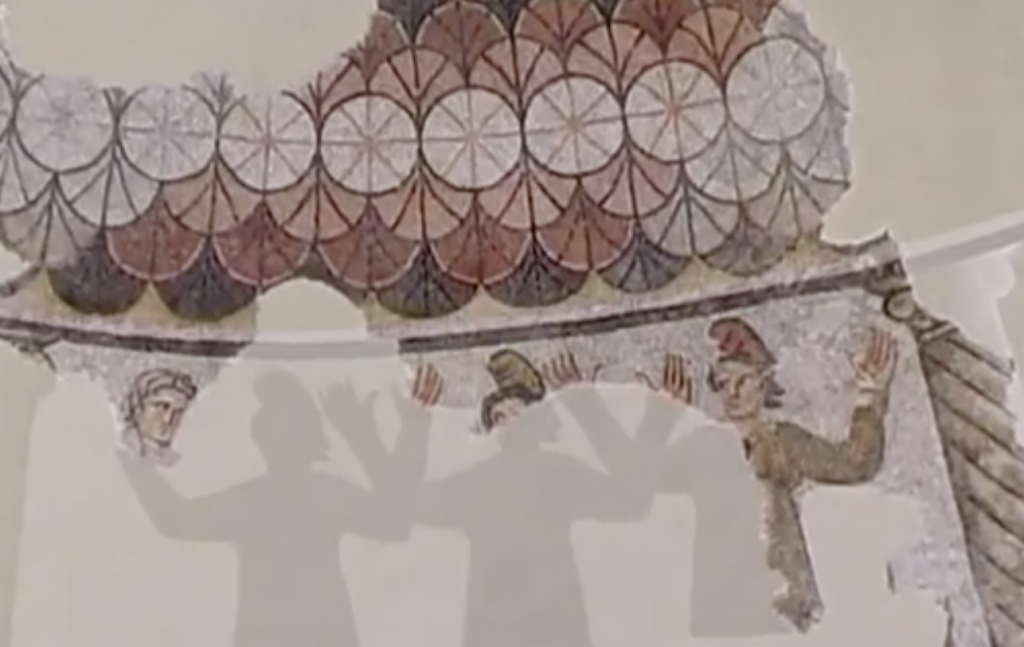

Centcelles, Roman building, used as a farm building

MacAulay wondered at how the Spanish let many of their ancient buildings fall into disrepair or be used for everyday purposes. In Centcelles, there stands a Roman villa, which contains what has been said is a ‘masterpiece of Early Christian Art’, the oldest dome mosaic with a Christian theme in the Roman world, dated to the 4th Century AD. At the time that Rose MacAulay visited the building was being used as a farm house, and the member of staff in the nearest tourist office, whilst knowing of its location had never visited it. MacAulay was taken aback by the importance of the building but astonished by its state and use.

Could it happen anywhere but in Spain that such a treasure from the antique past would be allowed to fall into ruin in the hands of farmer owners, instead of being acquired and preserved by the State or by some ancient building preservation society, and thoroughly explored?… It lies neglected and mouldering down the centuries, in this remote farm at the end of a rutted path.

Ten years after MacAulay visited, and one year after her death, the German Archeology Institute acquired the property, and excavated it. The excavations suggested that the Romans had built a villa and rural building dedicated to farming. One wonders what MacAulay would have made of the discoveries.

Architecture

Valencia’s Blue Church Domes

Rose MacAulay described blue church domes throughout the Valencia region. I was rather taken aback with this description and determined to find examples of them on the internet. They are indeed quite beautiful.

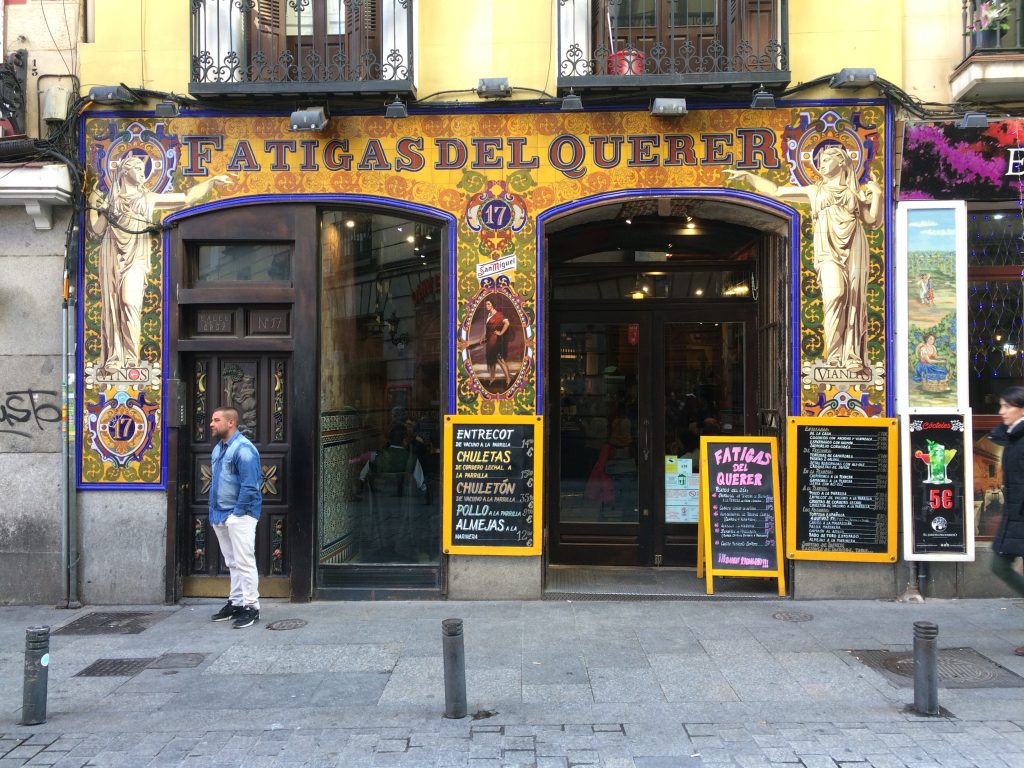

Azulejos

MacAulay frequently describes the azulejos of Spain. Azulejos are painted tin-glazed ceramic tiles. Today in 2020 they remain a feature of Spain’s facades, both exterior and interior. They are often very colourful or used to form a mosaic. They are, to my understanding, quintessentially Spanish.

The Cave Dwellers of Sierra de Guadix

Rose MacAuley described people living in the cliffs of an Andalusian town called Sierra de Guadix.

All about there were doors and chimneys in the cliffs, and behind the doors (sometimes painted blue) lived the cave dwellers. It was like a child’s picture book of gnomes’ houses, fantastically improbable and unreal.

The Ronda Gorge

Rose MacAuley mentioned the Ronda Gorge, which is a spectacular site, it has to be said, and I am surprised I have never seen it or heard of it before. The gorge is equalled by the bridge that was built to span the gorge.

It is a romantic thing to stand on a bridge and look across from an old Moorish town of the eighth century to an old Spanish one of the fifteenth.

Cadiz

I had always thought Cadiz was a Spanish city on the south coast, and it is, but I had never realised that it is in essence, an island, or at least part of a larger island, La Isla de Leon, that lies off the south coast.

Rose MacAulay called the road that ran across the causeway (the CA-33 on the map above) as one of ‘the lovely wonders of the world’ being built on arches and having the smooth blue of Cadiz Bay on one side and the ‘dancing silver immensity of the Atlantic’ on the other. Having had a ride along the road on Googlemaps it would seem that a more modern and less wondrous construction is in place.

Cadiz, MacAulay explained, has an ancient heritage being a site for Phoenicians, Carthaginians, Greeks and Romans. She paid Cadiz, which apparently was known to the Romans as Gades a one page homage.

The British in Spain

Throughout her book Rose MacAuley makes reference to the presence of the British in Spain. British business people, it appears, had made a significant investment in various food and drink industries, on the east and south coasts of Spain throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth century.

The English cemetery in Denia

The presence of so many British people and their being protestant, and for reasons of Spanish Catholic prejudice and discrimination, unable to bury their dead in Catholic cemeteries, meant that the British paid for and created their own cemeteries.

Rose MacAuley visited the English cemetery in Denia.

A white walled cypress garden above the sea, a century old, where raisin merchants and English sailors lie; the merchants have monuments and inscriptions, the sailors sleep nameless, beneath piles of stones.

Seventy years later, in 2020, the cemetery appears to have fallen into a state of disrepair (see here and here).

The Private Beach of an English general

One of the funniest entries in Rose MacAuley’s book was her thoughts on her experiences of coming across a part of the coast near to Gibraltar, which a member of Spain’s guardia civil had forbid her from entering, because it was apparently owned by an English general.

I asked if I might swim out from further down the shore and land on the rocks of the general; the guard said no, the general did not permit that one landed on his rocks. Does the general own the sea too? I asked Yes, the sea also was the general’s. For how far out? For two kilometres, replied the guard – further than I would wish to swim, and I agreed… It seemed that either that the cove was a gift to the English general from the Spanish nation, which, in view of Gibraltar, was generous; or that the general had, with true casual British imperialism, just annexed it, and engaged a guard to defend it. I felt my customary admiring pride in the exploits of my countrymen, and thought there should be a Union Jack flying over the beach.

Gibraltar

Rose MacAuley provided a great deal of information on Gibraltar, the fact of it being under British control and having a history that MacAuley was well read on, appeared to have been the two spurs. She provided a lot of information about how the British came to get hold of Gibraltar and the experience and effects on the local Spanish population.

In particular she pointed out that the British invaded and took Gibraltar in 1704. She noted that the behaviour of the British army was ‘atroicious’.

They seem, according to the contemporary records, both Spanish and British, to have become (as always when they took towns) excessively intoxicated, and to have rushed about sacking and looting houses, violating women and churches, attacking the many shrines and convents in which old Gibraltar abounded, and destroying and mutilating images and relics in an orgy of drunken lust, robbery, anti-popery and anti-Spanish triumph.

Six thousand Spanish fled from the town, leaving behind them a good many Jews, Genoese and Moors, who were prepared to adapt themselves and their commercial activities to any regime, and a few women, whose activities were also adaptable.

The Spanish people in Gibraltar fled and set up a new town, called San Roque some miles away, to the north and in the interior. Visiting in 1949 MacAulay noticed that many of the British people living in Gibraltar were Jewish, although she did not note whether they were the descendants of the old Spanish Jews, or newly arrived British Jews. MacAulay described Gibraltar, as a unique place, and not entirely British. She described the streets being full of shops selling ‘gaudy trash from the bazaars across the straits’, its ‘Main Street’ being, ‘a bright, fantastic nonsense, which seems to connect with no European country’. Taking a look at Main Street in 2020, it would seem not a lot has changed, although it might be argued, that for at least in London, many of the suburban shopping streets have slowly converged upon the style of shopping street first described by MacAulay in 1949 in Gibraltar. MacAulay also felt that the architecture of Gibraltar was business like, and in that sense British, in contrast to the picturesqueness of the Spanish plazas.

I do wonder what was going on in Gibraltar during the Spanish civil war, and whether anyone tried to escape over the border to flee Franco’s forces. I know the British government of the time were keen to avoid getting involved in the conflict, as they were keen, initially to avoid getting on the wrong side of Hitler. As far as I understand it, this was because the British were less bothered about ideologies and more bothered about protecting their own wealth and dominions, and so long as these were not threatened they were not going to make sacrifices.

Cadiz

The English had a keen interest in the south coast of Spain stretching as far back as the 1500s. In 1596, explained MacAulay, a chap named Essex with boat loads of English raiders, sacked Cadiz, and took back some hostages, for whom a ransom was demanded and obtained.

Jerez de la Frontera

Jerez de la Frontera, MacAulay explained, was a small rather charming Spanish town, in which the British had historically had a big presence. The principal interest in the town, historically, has been sherry. MacAulay noted that:

One agreeable effect of the presence of British residents in Jerez is that visiting British are more taken for granted than elsewhere in Spain, and do not get so followed about; the breed is familiar. Even female car drivers have doubtless been seen.

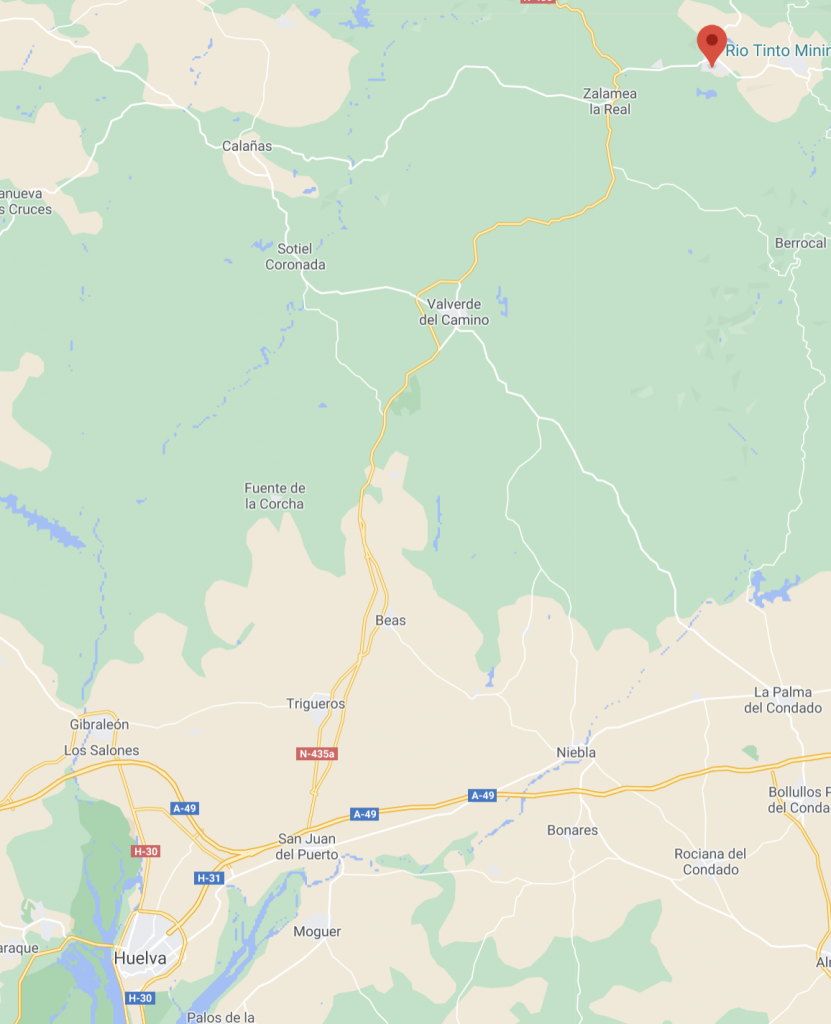

Rio Tinto

Not so far from Jerez de la Frontera is the River Tinto, called Rio Tinto. The name of this river immediately hit me, because it made me think of the giant mining company Rio Tinto Zinc. And there is a link! Rio Tinto Zinc, is an English Australian company, but it was founded in 1873, when a multinational consortium of investors purchased a mine complex on the Rio Tinto, in Huelva, Spain, from the Spanish government. Its successes in Huelva triggered one hundred of fifty years of growth and it now has its headquarters in Melbourne, Australia.

The actual mine would appear to be seventy kilometres north of Huelva, where the river opens out into the sea.

Before the mine was built I understand that the Rio was already named Tinto, owing to its rust colour. With the coming of the mine, the river must have darkened further I would imagine.

The Algarve, Portugal

I have never been to Portugal, so I was interested to see how MacAulay experienced the south coast of Portugal, as a continuation of Spain. Apparently Portugal is a lot cooler, receiving colder winds and seas from the Atlantic Ocean, compared with the south coast of Spain, whose weather comes from Africa and the comparative warmth of the Mediterranean. People from the Algarve, she said, ‘were less handsome, smaller and squatter, with faces more round and undefined, more of the negro, less of the Moor’.

Many of the women wore men’s bowler hats, tied under the chin with scarves; there were straw hats everywhere; men and women rose on donkeys with umbrellas up against the sun.

Post-Script

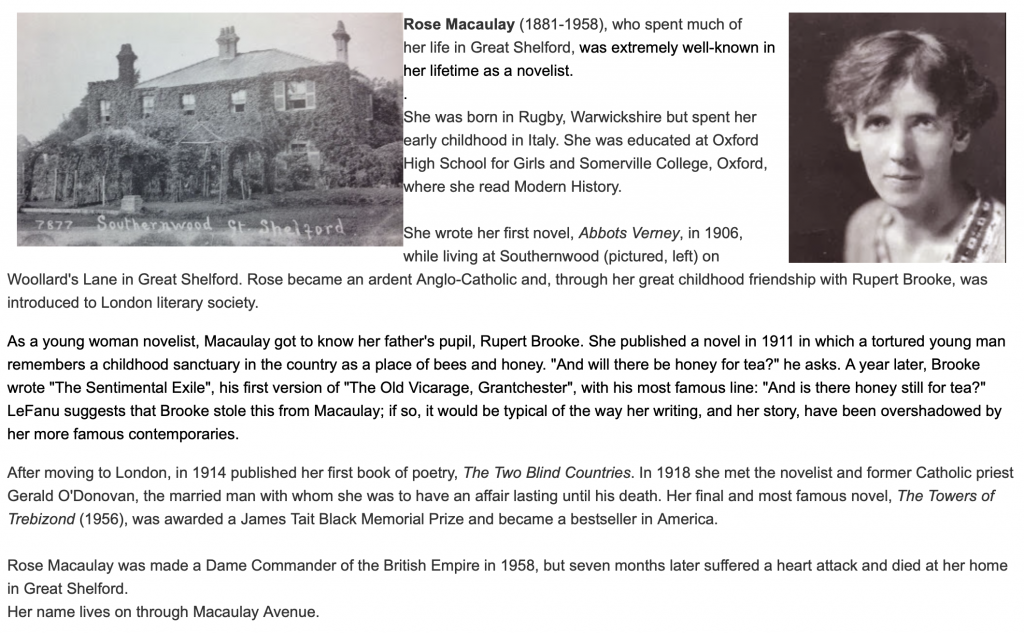

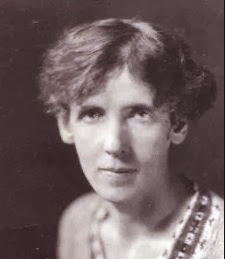

I found this article about Rose MacAuley, summarising her life. It contained a photo and a picture of the house she lived in, in Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire.

Southernwood, at 5 Woollard’s Lane in Great Shelford, is still standing. You can’t see it from Woollard’s Lane because it is located behind a number of large trees.

However the exterior and interior of Southernwood can be viewed in great deal in a publication created by an estate agent here.

Just a few miles from Southernwood, there’s a statue of Rupert Brooke, cast in some kind of metal it seems, in the drive way of a garden of a house in Grantchester, his family home I would imagine.

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/library/mrc/archives_online/digital/scw/timeline2/

Rose MacAuley’s entry on an encylopaedia website: https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/macaulay-rose-1881-1958